Equal access to public transportation is one of the cornerstones of the American with Disabilities Act. Despite being given ample opportunities and extensions, The National Passenger Railroad Corporation, also known as Amtrak, has failed to make itself inclusive of this broad segment of the population.

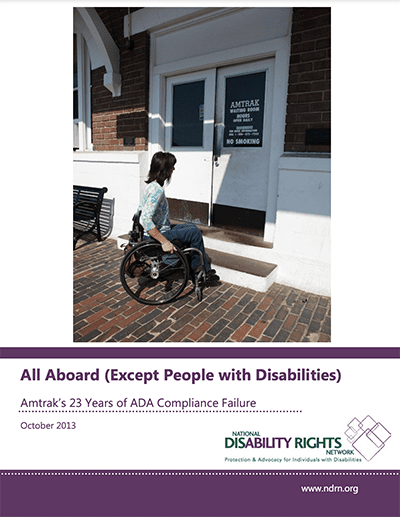

In this report, All Aboard (Except People with Disabilities), the Protection and Advocacy System investigated the state of passenger rail in the US. NDRN’s recommendations and suggestions are available in the conclusion section of this report.

Download “All Aboard (Except People with Disabilities” (PDF)

Transportation is the linchpin of community integration. Without it, many people with disabilities cannot go to work, go shopping, visit their friends and family, or accomplish many of the day-to-day tasks necessary to live in the community.

Unfortunately, progress in providing accessible transportation has been slow and has required legislation and tireless and consistent advocacy. Critical pieces of federal legislation such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Air Carrier Access Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act, were necessary to start the process of breaking down the barriers to buses, trains and airplanes so that people with disabilities could use these sources of transportation daily.

While many transportation providers around the country have shown that it is possible to provide accessible services for people with disabilities, one carrier – the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, or Amtrak – has lagged far behind. People with disabilities who travel on Amtrak have faced numerous barriers to using Amtrak. Some have faced inaccessible trains, others have been unable to purchase tickets to their destinations because the platforms and stations were inaccessible, and some have had to disembark at a station that was not their ultimate destination just so they could get off the train or out of the station. People with disabilities have also been forced to suffer embarrassment, discomfort, and other indignities due to a lack of accessible bathrooms and other facilities and services.

Congress recognized the numerous obstacles Amtrak faced to becoming accessible by giving them decades to achieve accessibility, much longer than other forms of transportation. Although Amtrak has repeatedly said that they are moving toward accessibility, this report shows that progress has been uneven, spotty, and in some cases non-existent. Most shocking is how blatant and obvious many of the accessibility issues demonstrated in this report are. Does it really take more than 23 years to provide a ramp into a station with only stairs, provide and properly mark accessible parking, and remodel inaccessible bathrooms and counters to make them accessible?

In July and August 2013, around the 23rd anniversary of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, advocates with the Protection and Advocacy network and allied advocacy groups visited Amtrak stations around the country to assess whether they are accessible for people with disabilities. They found many problems – many stations that are completely inaccessible and many stations where it is clearly difficult for people with disabilities to navigate, even 23 years after passage of the ADA.

We hope to move toward solutions. As the primary legal advocacy provider for people with disabilities, with years of experience monitoring accessibility in a variety of settings in every state and territory, the Protection and Advocacy network is well positioned to help enforce federal and state laws relating to accessibility of Amtrak stations. We are already at work – the Pennsylvania Protection and Advocacy agency, for example, has filed a lawsuit to make a station in their state accessible and NDRN has submitted reports of dozens of other inaccessible stations to the Department of Justice for further investigation and enforcement actions.

It is time for Amtrak to stop making excuses and start making its system accessible. People with disabilities have been waiting for too long.

Sincerely,

Curtis L. Decker, J.D.

Executive Director

Acknowledgements

SPECIAL THANKS TO THE FOLLOWING P&As FOR CONDUCTING REVIEWS AND PHOTOGRAPHING STATIONS

Advocacy Center (Louisiana)

Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program

Disabilities Law Program (Delaware)

disAbility Law Center of Virginia

Disability Rights California

Disability Rights Center of Arkansas

Disability Rights Florida

Disability Rights Montana

Disability Rights New Jersey

Disability Rights New York

Disability Rights North Carolina

Disability Rights Ohio

Disability Rights Oregon

Disability Rights Texas

Disability Rights Vermont

Disability Rights Washington

Indiana Protection and Advocacy Services

Michigan Protection and Advocacy Services

Minnesota Disability Law Center

Missouri Protection & Advocacy Services

North Dakota Protection & Advocacy Project

Protection and Advocacy for People with Disabilities, Inc. (South Carolina)

The Legal Center for People with Disabilities and Older People (Colorado)

University Legal Services (District of Columbia)

PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS

Rochester Center for Independent Living

THE FOLLOWING INDIVIDUALS CONTRIBUTED TO THIS REPORT:

Eric Buehlmann, Deputy Executive Director for Public Policy, National Disability Rights Network

Curtis L. Decker, Executive Director, National Disability Rights Network

Kenneth Shiotani, Senior Attorney, National Disability Rights Network

Patrick Wojahn, Policy Analyst, National Disability Rights Network

SPECIAL THANKS TO THE FOLLOWING:

Edmund Asiedu, Intern, National Disability Rights Network

Dennis Cannon, Synergy, LLC, Washington, DC

Bradley Harris, Law Intern, National Disability Rights Network

Christopher S. Hart, Director of Urban and Transit Projects, Institute for Human Centered Design, Boston, MA

Rose Sloan, Intern, National Disability Rights Network

The National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) is the nonprofit membership organization for the federally mandated Protection and Advocacy (P&A) Systems and the Client Assistance Programs (CAP) for individuals with disabilities. The P&As and CAPs were established by the United States Congress to protect the rights of people with disabilities and their families through legal support, advocacy, referral, and education. P&As and CAPs are in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. territories (American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and there is a P&A and CAP affiliated with the American Indian Consortium which includes the Hopi, Navajo, and San Juan Southern Paiute Nations in the Four Corners region of the U.S.

As the national membership association for the P&A/CAP network, NDRN has aggressively sought federal support for advocacy on behalf of people with disabilities, and expanded P&A programs from a narrow initial focus on the institutional care provided to people with intellectual disabilities in facilities to include advocacy services for all people with disabilities no matter the type or nature of their disability and where they live. Collectively, the P&A and CAP Network is the largest provider of legally based advocacy services to people with disabilities in the United States.

Today P&As and CAPs work to improve the lives of people with disabilities by guarding against abuse; advocating for basic rights; and ensuring access and accountability in health care, education, employment, housing, transportation, voting, and within the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Through the Protection and Advocacy for Voter Access program, created by the Help America Vote Act, the P&As have a federal mandate to “ensure the full participation in the electoral process for individuals with disabilities, including registering to vote, casting a vote and accessing polling places” and are the leading experts on access to the vote for people with disabilities in the U.S.1

“At its heart, the [Americans with Disabilities Act] is simple…. This landmark law is about securing for people with disabilities the most fundamental of rights: ‘the right to live in the world.’ It ensures they can go places and do things that other Americans take for granted.” – Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA)

Senator Tom Harkin, “Americans with Disabilities Act at 20: A Nation Transformed”

The promise of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which remains as vital today as it was when it was passed, was to ensure full integration of people with disabilities into every aspect of society. By prohibiting discrimination and ensuring accessibility of accommodations in employment, government services and public accommodations, the ADA took the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 one step further to require that all entities, public and private, provide access to people with disabilities on the same level as people without disabilities.

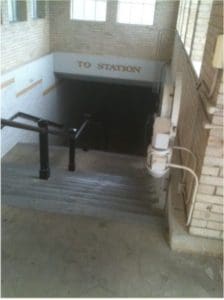

One entity in particular has failed in that promise. The National Passenger Railroad Corporation, also known as Amtrak, has received many opportunities from Congress and the Departments of Transportation and Justice to come into compliance, including an extra twenty years to make its stations accessible. However, three years after the twenty year extension, there remains much to be done. Some of the glaring barriers are things that should not have taken 23 years to make accessible. Does it really require that long to install a ramp to a station entrance so that a person using a wheelchair can actually get into the station?

After 23 years, Amtrak should be a shining example of accessibility. Instead, some stations appear to have had no work done to even make the front doors and restrooms accessible. There are many platforms and parking lots where Amtrak appears to have done little to provide or maintain accessible parking and paths into the stations and to the platforms. Even where designated parking spaces have been marked and accessible routes created, Amtrak has not commonly maintained them. For individuals who are deaf, many Amtrak stations that provide audio announcements of train status fail to provide complementary visual notification even when the equipment to do so is available at the station. For individuals who are blind, many station platforms lack detectible warnings at the platform edge and accessible communication such as announcements made over loudspeakers or corresponding braille text on all signs.

These barriers matter. Many people with disabilities, unable to drive, rely on public transportation to get to work, to visit their families, for day-to-day life activities. Rural areas in the United States have been losing access to other modes of public transportation, meaning that people with disabilities must rely more than ever on the services that remain. U.S. carriers cut domestic flights by over 21% in small airports between 2007 and 2012,[1] and intercity bus transportation coverage declined from 89 percent in 2005 to 78 percent in 2010.[2]Where Amtrak provides service, it can be a lifeline that allows people with disabilities to live full and active lives, and gives them the freedom to travel. Even in more urban areas, where more options for travel exist, Amtrak provides other ways to commute or more easily travel around the region.

Amtrak, which calls itself “America’s Railroad,” should set an example of full accessibility for people with disabilities. As the nation’s largest passenger rail system, it should be the gold standard for how to best serve people with disabilities, not the bottom of the barrel. In fact, since many commuter trains stop at Amtrak stations, making Amtrak stations fully accessible would help make commuter rail accessible as well.

This report discusses the history of how Amtrak has failed people with disabilities by failing to effectively use the hundreds of millions of dollars it has received to comply with the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Then, the report examines the findings of disability rights advocates who, during the summer of 2013, evaluated Amtrak stations for obstacles that people with disabilities face when they attempt to use the system. Although these advocates looked at only a sample of stations, the barriers they found are barriers that people with disabilities confront all across the country every day.

[1] Geewax, Marilyn, “Smaller Airports Take Bigger Hit As Airlines, Cut Flights,” May 8, 2012, available at <http:// www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2013/05/08/182262805/smaller-airports-take-bigger-hit-as-airlines-cut-flights>.

[2] Bureau of Transportation Statistics, The U.S. Rural Population and Scheduled Intercity Transportation in 2010: A Five-Year Decline in Transportation Access, February 2011, available at < http://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/sites/ rita.dot.gov.bts/files/publications/scheduled_intercity_transportation_and_the_us_rural_population/2010/pdf/entire.pdf>

Like the entire bill, the Americans with Disabilities Act’s (ADA) provisions regarding the accessibility of rail transportation were a product of negotiations and compromises. Early versions of the legislation called for all intercity rail stations to be accessible within three years after the date of the enactment of the ADA. When first introduced in 1989, the legislation included a provision to allow passenger railways a 20-year extension for a station if the Secretary of Transportation found that the station required extraordinarily expensive structural changes to be brought into compliance. Later amendments required commuter rail transportation systems to make key stations accessible within three years with the possibility of a 20-year extension when extraordinarily expensive structural changes were necessary. Ultimately the law provided a blanket 20-year extension for intercity passenger rail (Amtrak) while requiring it to make all of its stations accessible as soon as practicable. The 20-year extension was the longest provided to any entity under the ADA.

A May 15, 1990 report of the House Committee on Education and Labor summarized the requirements for intercity rail stations under Amtrak as follows:

Intercity rail systems, including the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, must be made accessible as soon as practicable, but in no event later than 20 years after the date of enactment. Key stations in rapid rail, and light rail systems must be made accessible as soon as practicable but in no event later than three years after the date of enactment of this act, except that the time limit may be extended by the Secretary of Transportation up to 20 years for extraordinarily expensive structural changes to, or replacement of, existing facilities necessary to achieve accessibility.

“Amtrak is required to make all stations in its systems readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities, including individuals who use wheelchairs, as soon as practicable but in no event later than 20 years after the date of enactment.”

–House Committee on Energy and Commerce, May 15, 1990

For decades, Amtrak has stalled and made excuses for its failure to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Some of the justifications have included: 1) that level boarding is difficult to achieve 2) that it often does not own the stations that it serves and therefore only has a shared obligation to make them accessible; and 3) that it lacks federal funding necessary to make the stations and trains accessible. Although there may be some challenges to obtaining full accessibility, these are obstacles that Amtrak has had more than two decades to overcome. In fact, Congress recognized these difficulties and that is why Amtrak ended up getting the 20 year compliance extension, the longest of any public service. Amtrak needs to stop making excuses and do the work necessary to come into compliance.

Level-boarding is possible and enhances station usability for everyone.

Level-boarding, meaning being able to get on and off a rail car without the use of steps or lift, is the safest, most operationally efficient and maintenance free option for providing access to all passengers. It allows all passengers to get on and off the trains faster, meaning less time to wait at a station. This is especially important with the development and growth of high-speed rail. Accessibility through level boarding benefits many other people, not just people using wheelchairs, such as families with baby strollers, the elderly, and passengers carrying luggage.

A variety of options exist for Amtrak to allow for level-boarding and Amtrak has been able to provide full level boarding at a number of stations. Like the installation of curb cuts, level boarding will have benefits beyond just increasing the accessibility of trains for people with disabilities. Amtrak should be a shining example of accessibility, and this includes providing level boarding.

Accessibility can be achieved even where Amtrak does not have full ownership of the building, parking lot, platform, etc.

Amtrak has consistently pointed to the fact that they do not have full control over many stations that it serves as a reason for failing to make their services accessible. Congress recognized this was an issue back when the ADA was passed which is why Amtrak was given 20 years to come into compliance with the ADA requirements. Congress also created a formula to allow other joint station owners to equitably share in the costs of making the stations accessible, even while Amtrak maintained primary responsibility. Amtrak could have spent the twenty additional years they had to come into compliance with the ADA working with local transit authorities, freight carriers and state and local entities to address these issues. Instead, Amtrak chose to wait until the 20 years was almost over and then say they had no time to work with others to make the stations accessible.[1]

Although this ownership can present challenges to obtaining accessibility, many of these other owners – whether state or local governments or private companies – are under the same obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (and often the Rehabilitation Act) to provide accessible service. It was incumbent upon Amtrak to coordinate the sometimes multiple players at each station necessary to achieve an accessible route into the stations and onto the trains, rather than wait almost 20 years and then complain about the difficulty of coordinating the owners. In fact, some stations that have become accessible have done so because other owners, such as New Jersey Transit in Trenton or the Capital District Transit Authority in the Albany-Rensselaer stations stepped forward and built stations where people with disabilities can access Amtrak trains, with little to no support from Amtrak.

Amtrak has received federal funding specifically dedicated for accessibility

Over the course of 23 years since the passage of the ADA, Amtrak has received federal funds which include a requirement to not discriminate and thus renovate and rehabilitate its stations to be accessible. In recent years, when it was clear Amtrak would not be fully compliant by 2010, Congress directed Amtrak to use specific amounts of its federal funds for accessibility improvements. [2]

Amtrak also received stimulus funds, but as this report shows, it has failed to make much progress. In fact, there are examples where Amtrak has increased accessibility at a station by installing a new platform or accessible parking, but then has gone back and redone the same items again at the same station with no gain in accessibility rather than making needed improvements at an inaccessible station where no work has been done.

Amtrak has failed to make some basic and inexpensive modifications at many of its stations, such as installing ramps when necessary and ensuring that ticket counters are low enough for people who use wheelchairs. Often, Amtrak has simply failed to provide accessible stations even when it could be easily done. In this time of limited federal resources, it is incumbent that funds be used in an efficient manner to maximize the increase in accessibility, and we would argue that Amtrak has not done that with the funds it has received.

Amtrak’s own Office of Inspector General notes lack of progress

Amtrak’s own Office of Inspector General (OIG) conducted an investigation to assess Amtrak’s noncompliance with the ADA’s requirement to make all its stations accessible by July 2010. The OIG report noted that “Since 1990 Amtrak has made very limited progress in making its stations ADA-compliant, only 10 percent of served stations required to be compliant were reported as compliant.”

Unfortunately, the NDRN report confirms the findings of the September 29, 2011 OIG Report and shows that very little has been done since that time to make Amtrak comply with the ADA requirements.

The OIG report notes that “In February 2009, Amtrak reported that 48 stations servicing 34 percent of the FY 2010 ridership were ADA compliant. Almost 2½ years later, no additional stations have become ADA-compliant, leaving 434 stations that have not yet been deemed ADA-compliant.” The OIG Report also noted that while Amtrak had developed a survey assessment to identify the work needed to bring all Amtrak stations into ADA compliance and had completed 77 out of 104 stations to be evaluated in FY 2011, and some design work had been done, no construction contracts had been awarded as of September 30, 2011. The OIG Report concludes that “Amtrak’s approach to managing the ADA program lacks clear lines of authority, responsibilities, and accountability.”

[1] Amtrak’s February 1, 2009 Report on Accessibility and Compliance with the ADA admits that in a survey of its compliance18 years after passage of the ADA only 48 out of 481 stations was 100% compliant with the ADA, and that by 2013, assuming adequate funding, only 269 of its stations would be 100% ADA compliant.

[2] See, e.g., P.L. 112-55, Consolidated and Further Continuing appropriations Act, 2012, at 109 (requiring that $50 million of the $952 million allocated toward Amtrak infrastructure improvements be dedicated specifically to bringing Amtrak facilities in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act).

The ADA and the Department of Justice and Department of Transportation regulations require specific architectural and communication accommodations to allow people with a wide range of disabilities, including wheelchair users, the ability to readily access train stations and railcars. The requirements address accessibility for people who use wheelchairs to parking areas, loading zones, travel paths, doorways, ticket counters, and restrooms. The regulations also require accessible methods of communication for people with sensory disabilities.

Some of the specific ADA requirements include:

- Providing a minimum number of accessible parking spaces, including a space with an extra-wide aisle to allow a person with a disability who uses a van with a lift to get in and out of the van

- Ensuring that accessible parking areas are not on an incline

- Requiring that curb cuts or ramps allow a wheelchair user to get from the accessible parking space into the station building

- Requiring ramps or elevators so that individuals with disabilities who cannot climb stairs have access to all levels of the station

- Requiring that doorways are wide enough and have thresholds that are low enough so a wheelchair user can get through

- Requiring that signs that direct individuals with disabilities to the accessible entrance or restrooms have corresponding braille text

- Requiring restrooms to be have room for a person who uses a wheelchair to maneuver and use all the facilities

- Requiring signs and other communications to include alternatives that are accessible to individuals with sensory disabilities like vision impairments or deafness

- Requiring detectible warnings (truncated domes or edge protection) to allow individuals who are blind or visually impaired to know when they are getting close to the edge of a train platform

Photo 1: Platform lift in use at Florence station in South Carolina. |

Stations must also provide accessible means of boarding the trains. This can be done by providing raised platforms that allow for level boarding of the train. Most stations have rail platforms at or below the level of the tracks, however, and the floor of an Amtrak railcar is typically either 15” or 48” above the top of the rails. At these stations, Amtrak’s solution is to provide a portable manual lift as the means to achieve boarding. However, there are still some stations that do not provide even this basic means of access.

Staff from the P&As including attorneys, investigators, support staff, summer law clerks and interns, from 25 states and the District of Columbia, visited 94 Amtrak stations throughout the country during the summer of 2013.

Photo 2: Cleveland station reviewers. |

With a few exceptions, the P&A’s primarily visited Amtrak stations that included a station building. They surveyed parking lots, the path from the accessible parking spaces to the station, sidewalks, entryways, hallways and corridors, ticket counters, restrooms, and train platforms.

The technical expertise on architectural accessibility of the P&A staff visiting stations varied. Some were very familiar with accessibility surveys while many were not. Most P&As used a survey instrument adapted from the Department of Justice ADA Checklist for Polling Places Survey instrument. The Indiana P&A developed and used its own survey instrument.

Some P&As did not do formal surveys but took photographs of inaccessible features in the Amtrak stations, including restrooms, stairs and steps with no ramps, parking areas and platforms.

Some of the P&A agencies went so far as to produce their own reports. The P&A in North Carolina had already been surveying Amtrak stations on its own and created narrative reports about the surveys. The Virginia P&A created narrative reports of its visits focusing on the presence or the lack of presence of visual train information displays for passengers who are deaf, and noting obvious barriers to physical accessibility.

While the P&As visited 94 different Amtrak stations, a number of station buildings and platforms could not be surveyed because the stations were only open at set times when trains were arriving or departing, sometimes only in the overnight hours.

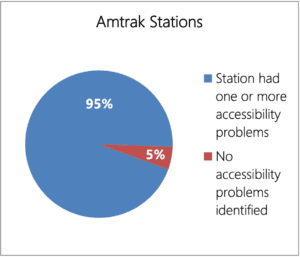

What the P&As Found

P&A staff found a wide and varied range of barriers to accessibility in these stations. Of the 94 stations visited, 89 were found to have one or more barriers to accessibility. The P&A staff found no ADA physical architectural accessibility issues at only 5 stations: Sanford, FL, Trenton, NJ, Lynchburg, VA, Culpepper, VA and Durham, NC stations. However, the Culpepper and Durham stations both lacked visual passenger information display equipment. It should be noted that the fact that the P&A staff who visited these stations did not identify any accessibility issues does not mean the stations are 100% compliant with the ADA. It just means the P&A staff, none of whom are “expert” ADA compliance surveyors, did not notice any accessibility issues.

In a handful of stations, the P&A staff did not find any barriers to access to people with mobility impairments. Most of these stations were new – for example, P&A staff who visited the Trenton New Jersey Transit Center (completed in 2008) and the Albany Rensselaer train station (completed in 2002) did not find any significant structural barriers. Even at these stations though, the P&A staff found some impediments to access. In Trenton, police and delivery vehicles repeatedly interfered with passenger drop-off areas and accessible walkways, while in Albany, the staff found that the accessible parking spaces were not at the closest location to the station’s accessible entrance as required under ADA regulations.

P&A staff also found some older or historic stations to be accessible. For example, in Virginia, staff found the historic station in Lynchburg to be largely accessible.

Amtrak’s second busiest station, Union Station in Washington, DC was found to be mostly accessible, but Amtrak has yet to provide elevator access to the platform for tracks 27 and 28, which serve trains travelling south of Washington, DC. Passengers with mobility disabilities boarding or detraining from trains using Tracks 27 and 28 need to wait for carts to take them from the platform to the station building or vice versa via a long, circuitous route.

Some stations were shockingly inaccessible 23 years after the passage of the ADA. In Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Malta, Montana, Longview, Texas, St. Albans, Vermont and Ashland, Virginia the station buildings had a step or steps into the station building with no ramps. Restrooms in those stations were completely inaccessible, with no grab bars or other accessible features.

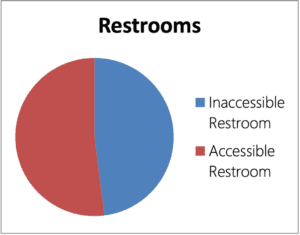

In fact, restrooms remain a considerable problem throughout Amtrak’s system. Of the stations visited by P&A staff that had restrooms, nearly half were found to have barriers to accessibility.

The Rochester, New York station, built in the late 1970s, has its accessible parking spaces right next to the building. However those spaces are on a significant slope and thus are difficult for a person in a wheelchair to use and do not comply with ADA requirements. The restroom stalls in the Rochester station also lack grab bars and are too narrow for a wheelchair user to enter. The restrooms lack accessible sinks, soap dispensers and paper towel dispensers, and appear to be unchanged from the date of construction in the late 1970s. The Rochester station, which serves the National Institute for the Deaf at the Rochester Institute of Technology and a large deaf community, also lacks any electronic visual train information signs to complement the audio loudspeakers. The only visual train information was on a manual letter board.

Three stations visited by the P&As stand out for special mention: Marshall, Texas, Newark, Delaware, and Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. These three stations have no accessible path for a wheelchair user to get from one platform to the other. The only way to the opposite platform at these stations is a stairway and a tunnel or bridge and another stairway.

Photo 3: This tunnel is the only access between platforms at Harpers Ferry station. |

P&A staff also found other major barriers to accessibility in a number of stations. A significant number of stations lack accessible parking spaces, have doorways with high thresholds, or have narrow doors. An even larger number of stations have restrooms that are largely or completely inaccessible for people who use wheelchairs. Finally, a number of stations have sidewalks or walkways that have so deteriorated that they pose a barrier to accessibility.

In addition to these more significant barriers to accessibility, many stations have door hardware that is difficult or impossible for an individual with limited dexterity to open. Many others do not have accessible ticket counters. Many stations have faded markings for accessible parking spaces, or uneven pavement on their sidewalks, parking lot, pathways or ramps. Platforms at a number of stations are in poor condition and many lack detectible edge protection.

Even when stations did have visual train display capability, it was not being used. P&A staff were not able to determine whether this was due to a mechanical problem or the failure of station staff to use the equipment.

AMTRAK

- Prioritize and address basic barriers to accessibility like steps with no ramps, narrow doors, high thresholds, lack of accessible parking spaces, barriers to accessible routes and missing detectible platform edge warnings.

- Provide electronic train information equipment and teach and require station staff to use the equipment to provide dual mode communications.

- Collaborate and fund P&As to help identify accessibility issues at stations nationwide.

- Build raised platforms for level-boarding in any new or rehabilitated station. Work with freight carriers to accommodate freight carriers alongside stations with raised platforms.

- Improve accessibility of Amtrak’s web and telephone reservation system for people with disabilities.

- Finish what it should have completed three years ago, have a fully accessible intercity passenger rail system.

CONGRESS

- Utilize Congressional funding authority to enforce accessibility requirements for Amtrak.

- Require level boarding at all Amtrak stations in order to increase accessibility for all people to Amtrak trains.

- Fund Protection and Advocacy agencies to monitor and provide technical assistance to all stakeholders in order to achieve full accessibility at all Amtrak stations.

- Hold a hearing to bring attention to the failure of Amtrak to meet accessibility requirements at its stations, in its trains, and throughout its provision of services.

- Include strict accessibility requirements in the next Amtrak reauthorization with consequences for failure to meet these requirements.

ADMINISTRATION

- Department of Justice’s Disability Rights Section and Department of Transportation’s Federal Railroad Administration Office of Civil Rights must meet with Amtrak and develop a plan to reach full accessibility compliance promptly.

DISABILITY COMMUNITY

- Ride on Amtrak trains, even with Amtrak’s problems, as Amtrak needs to see that people with disabilities are an important part of their market. Report and file complaints with the Department of Justice Disability Rights Section, Amtrak and the Federal Railroad Administration’s Office of Civil Rights if you run into barriers at stations or onboard the trains.

- Provide input to the Access Board’s Rail Vehicle Advisory Committee, which is about to start a process to develop new accessibility guidelines for new railcars.

Specific findings by state

Alabama

Alabama P&A visited the Birmingham and Tuscaloosa stations. In Birmingham, restrooms appeared to be inaccessible, there was a steep ramp to the front entrance, and a freight elevator was used to access the passenger platform.

Photo 4: Ramp at Birmingham station. |

In Tuscaloosa, steps were needed to access the station and there was no ramp (cover photo). The restroom lacked grab bars and was too narrow for a wheelchair user to access, among other accessibility problems.

Photo 5: Inaccessible restroom in Tuscaloosa station. |

Arkansas

The Arkansas P&A visited the Arkadelphia, Hope, Malvern and Texarkana stations.

In Arkadelphia, they found uneven pavement in the ramp. The ramp also crosses into the path of travel (see photo).

Photo 6: Ramp crossing into path of travel at Arkadelphia station. |

The restroom in the newly opened Hope station appeared not to be fully compliant with ADA accessibility requirements. One of the accessible parking spaces was at a slope due to a drain. There was also no accessible ticket counter.

In Malvern, P&A staff found deteriorated paving.

Photo 7: Crumbling ramp at Texarkana station. |

In Texarkana, there was no marked accessible parking and a crumbling concrete ramp led to an abrupt level change at the base of the ramp. The P&A also noted that at Texarkana station the restroom stalls appeared to be accessible but the restroom doors were too heavy.

California

The California P&A visited the Sacramento station which continues to undergo significant reconstruction. They noted that the accessible parking was a significant distance to the station entrance. They found construction scaffolding and trash receptacles and other objects complicating travel paths throughout the station. A major concern was the very long distance between the station and relocated platforms (See photo series below). While carts were available for passengers, it appeared only one cart could accommodate a wheelchair user and that cart appeared to be locked and not in use.

Photo 8: Travel path to platform |

Photo 9: Travel path to platform (continued). |

Photo 10: Travel path to platform (continued). |

Photo 11: Travel path to platform (continued). |

Colorado

Colorado P&A visited the Denver and Grand Junction stations. While the Denver station is only a temporary station, the P&A found no accessibility problems. The only potential issue noted by the Colorado P&A was a heavy restroom door. At Grand Junction, they found uneven pavement and inadequate marking of the accessible parking spaces.

Delaware

The Newark, Delaware station has no station building but rather is just two platforms on opposite sides of the busy Northeast corridor. The only means to get to and from the northbound and southbound platforms is a set of stairs going to a bridge that crosses the tracks.

Photo 12: A stairway and bridge on left are the only way to get from one side of the platform to the other. |

District of Columbia

Twenty five years ago Union Station was restored and rededicated as a train station after an ill-advised attempt to make it a visitors center. P&A staff found it to be mostly accessible. However, access to the platform serving tracks 27 and 28, which serve trains going south to the Carolinas and Florida and other southern destinations, continues to lack an elevator. Thus, passengers heading south or detraining from trains using tracks 27 and 28 must wait for carts operated by Amtrak personnel that take a circuitous route out along uncovered portions of the platforms and crossing tracks to get to and from the station.

Florida

The Fort Lauderdale station was under construction but did provide accessible portable restrooms.

The Deerfield Beach station had a heavy door.

Photo 13: Paper towel dispenser out of reach at Kissimmee station. |

The Hollywood station pavement contained many abrupt level changes that pose barriers to people using wheelchairs or with other mobility impairments.

Kissimmee station had a completely inaccessible restroom and did not have an accessible ticket counter.

Lakeland’s parking lot and Orlando’s restroom appeared to not be fully accessible.

Photo 14: No clearance to access sink at Kissimmee. station. |

Tampa station had significant uneven pavement.

Winter Haven had no accessible restroom and no accessible ticket counter.

Photo 15: No grab bars in restroom at Kissimmee. station. |

Indiana

Photo 16: Parking lot of Waterloo station. |

The Elkhart, Indiana station had no marked van accessible spaces and an irregular brick path of travel. The ramp to access the entrance had a landing that was not compliant with ADA size requirements. And, the station entrance doorway had a high threshold. Inside, the restroom door was too narrow for a wheelchair user to access and the stall that was supposed to be an accessible stall did not comply with ADA size requirements.

The Indianapolis station lacked an accessible ticket counter. The doors to the restrooms were excessively heavy and some of the hardware in the restroom stalls was not accessible.

The Lafayette, Indiana station was generally accessible but did not have an accessible ticket counter.

The South Bend station’s main entrance was not accessible, and the station lacked an alternative accessible entrance. It also lacked an accessible ticket counter. The restrooms had heavy doors and lacked sufficient turning space in the restroom and the stalls. Access to the platforms was across one or two tracks that had large flange gaps and there was no sign of a platform lift.

The Waterloo, Indiana station had a gravel parking lot with no accessible parking spaces marked and no accessible route to the station. The platform lacked detectible warnings.

Louisiana

Lafayette’s Amtrak station had non-compliant handrails on the ramp into the station (there was a post between the ramp and the handrails); an abrupt level change between the waiting room and the platform; and a heavy door between the station and the platform.

Maryland

While the BWI Amtrak station was largely accessible, a trash can that appeared to be not movable partly blocked wheelchair access into and out of the women’s restroom.

Photo 17: Trashcan obstructing pathway to women’s restroom. |

Minnesota

The Detroit Lakes station was closed at the time of the visit. However, the station did not appear to have a platform lift.

The Red Wing station’s accessible parking space lacked an access aisle and a ramp did not have a proper handrail. The station entrance door hardware was too low. The restroom stall had an unusual grab bar configuration and was clearly too narrow for a wheelchair user.

Photo 18: Inaccessible bathroom stall at the Red Wing station. |

The St. Paul station’s parking lot did not have sufficient accessible parking spaces, the spaces did not appear to be sufficiently level and the parking lot paving was deteriorated. The station’s power doors closed very quickly and the station lacked an accessible ticket counter.

The Winona station seemed largely accessible but there was no sign of a platform lift.

Photo 19: Unlevel parking space at St. Paul station. |

Missouri

Photo 20: The accessible parking space at the Jefferson City station is located on a slope rather than a flat surface. |

At the Jefferson City station, the restroom lacked adequate clear space for a wheelchair. The toilet bowl was too low and the toilet paper holder was too high. The station’s accessible parking spaces were on a steeply sloped street.

Photo 21: This restroom stall at Jefferson City station is too narrow for a wheelchair. |

Montana

The Browning station was closed at the time of the visit but appeared to have a high doorway threshold.

The Cut Bank station had totally inaccessible restroom stalls, a very old inaccessible sink, high door threshold and inaccessible hardware on the entrance door handle.

The East Glacier station was not open at the time of the visit.

The Essex flag stop station is just a platform behind the Izaak Walton Inn and no survey was done.

Photo 22: Restroom stall too narrow to fit a wheelchair at Glasgow station. |

The Glasgow station’s accessible parking space markings were faded and there was no crosswalk marking from the accessible parking spaces to the station. The restroom stalls were too narrow and the grab bars were mounted too high.

The Havre parking lot was being resealed on the day of the visit so it is uncertain whether markings for the accessible parking spaces will be done properly or not. The ramp to the station entrance was slightly too steep and did not have handrails. The restroom stalls were too narrow.

The Libby station was not open at the time of the visit.

Photo 23: This step makes the entrance to the Malta Station inaccessible. |

The Malta station had a new accessible parking slab on what was otherwise a gravel parking lot. There was a step with no ramp at the station entrance and the door had a doorknob which could be difficult for a person with dexterity limitations to use. The restroom was too small for a wheelchair user to access and the grab bars were mounted too high. The sink had no clearance space underneath to allow a wheelchair user to use.

The path of travel to the Shelby station was over a set of old tracks that had large gaps and some otherwise deteriorated paving.

Photo 24: Narrow restroom stall and inaccessible sink. |

The West Glacier station had a relatively new, low platform, but P&A staff were told that the platform which is only about 25 feet long was often used by a train that did not line up with the length of the platform.

The Whitefish station lacked scald protection under the sink in the restroom. The station did not have an accessible ticket counter.

Photo 25: Shelby station travel path. |

New Jersey

Photo 26: Truck partially blocking curb cut. |

Photo 27: Police vehicle partially obstructing curb cut and obstructing view and parked in “No Parking Passenger Drop Off Area.” |

The Trenton Transit Center was largely accessible but police and delivery drivers often made accessible elements inaccessible by blocking curb ramps, passenger drop off areas and pedestrian walkways with their vehicles.

Photo 28: Truck obstructing view from curb cut. |

New York

Albany Rensselaer station was largely accessible, but the marked accessible parking spaces were not those closest to the accessible entrance to the station as required under the ADA regulations. Once pointed out to them by the P&A staff, the manager of the Capital District Transit Authority promised the P&A to have the parking spaces remarked promptly.

Photo 29: Accessible parking spaces at the Rochester station on a slope. |

Photo 30: Restroom stall at the Rochester station is too narrow for a wheelchair user, lacks grab bars and has a toilet paper holder mounted too high. |

The Rochester, New York, station built early in Amtrak’s history in the late 1970s, had its accessible parking spaces next to the building. However those spaces were on a significant slope and thus do not comply with ADA requirements. A sloped surface in an accessible parking space makes it much more difficult for an individual who uses a wheelchair to get in and out of his/her vehicle and makes transfers onto and off of a wheelchair very difficult. The restrooms in the Rochester station also lacked grab bars, were far too narrow for a wheelchair user to enter and the rest of the restroom lacked an accessible sink, soap and paper towel dispenser. The restrooms appeared to be unchanged from the date of construction in the late 1970s. The Rochester station which serves the National Institute for the Deaf at the Rochester Institute of Technology also lacked any electronic visual train information signs to complement the audio loudspeakers. The only visual train information was on a manual letter board.

North Carolina

The Burlington North Carolina station had faded parking lot markings.

A barrier wall in the Cary station restroom could prevent a wheelchair user from opening the door to exit the restroom. In addition, the parking lot failed to demarcate an accessible route across a lane of traffic from the accessible parking spots to the entrance.

The Charlotte station had insufficient accessible parking, uneven level changes and lacked a visual fire alarm. The accessible restroom was locked during ordinary business hours. The station also did not have an accessible ticket counter.

The Durham station had no visual information to accompany the audio public address system.

The Fayetteville station had insufficient accessible parking and lacked markings for the accessible route. The station also did not have an accessible ticket counter.

The Gastonia station had deteriorated accessible parking lot markings and routes. The restroom, which was visible even with the station closed, lacked grab bars. There was no platform lift. The station, as a whole, was in general disrepair.

The Hamlet station had antique train carts on the platform that, if relocated, could pose hazards to blind passengers.

The Greensboro station had confusing accessible routes of transit,insufficient signage, and inaccessible restroom doors. Access to the platform was not permitted without a ticket.

The High Point station was inaccessible from the parking area due to a high threshold into the station building and heavy door. Again, the P&A had no access to that platform.

The Kannapolis station had insufficient accessible parking, an inaccessible route to the station and inaccessible door hardware to the entrance door.

The Raleigh station had ramps that did not comply with ADA requirements, had faded parking lot markings and had a too narrow station entrance door. In addition, the station lacked an accessible ticket counter.

The Rocky Mount station had narrow doors, inadequate signage and slopes in the parking lot. The restroom appeared to not comply with ADA standards.

The Salisbury station had no van accessible parking spaces, the accessible route to the station was in poor condition and the restroom was not fully compliant with ADA requirements.

The Smithfield Selma station had inadequate parking marking, the back door to the platform had a high threshold and the restroom doors were too heavy.

The Southern Pines station ramp had no edge protection and an entrance with a high threshold. There was no accessible ticket counter. The restroom configuration made it inaccessible, even though it had grab bars and some turning space.

The Wilson station had a curb cut from the parking lot that was too steep and the accessible restroom elements were not compliant with ADA requirements.

Photo 31: This stall at the Williston station is too narrow for a wheelchair user to access and lacks grab bars. |

North Dakota

The Williston station restroom was too narrow for a wheelchair user to access and lacked grab bars.

Ohio

Photo 32: The restroom at the Cleveland station seen in this photograph is not accessible. |

The Cincinnati station’s accessible parking spaces were not in the location closest to the accessible entrance. There were abrupt level changes on the path of travel and narrow entrance doors.

The Cleveland station had faded accessible parking markings, protruding objects, no accessible ticket counter, no braille on the signs, no visual fire alarms and inaccessible restrooms with stalls too narrow for a wheelchair user.

The Toledo station was closed at the time of the visit but there was no sign of a platform lift.

Photo 33: Inaccessible ticket counter at the Portland station. |

Oregon

Portland station did not have an accessible ticket counter or an accessible counter in the baggage area.

The Salem station had inaccessible door hardware, no accessible ticket counter, and heavy doors to the platforms and restrooms.

South Carolina

Photo 34: Steps at the entrance of Charleston station make it inaccessible. |

The Charleston station lacked properly marked accessible parking and has totally inaccessible restrooms.

The Florence station had faded accessible parking markings and a questionable route from the parking lot to the station due to an inadequate curb cut.

The Kingstree station had no van accessible space and a large bench in the waiting room blocked the waiting room entranceway.

Texas

The Houston station’s parking lot markings were faded, the entrance appeared to be too narrow and the station did not have an accessible ticket counter.

The Longview, Texas station had steps with no ramp into the building, a broken curb cut in the parking area, and insufficient accessible parking spaces. At the time of the visit, construction equipment was parked in the accessible spaces. The station was closed at the time of the visit so there is no information about the interior of the station.

Photo 35: Inaccessible entrance to the Longview station. |

The Marshall, Texas station was totally inaccessible with no apparent accessible pathway to the station from the parking lot. There was only a stairway from the parking lot area that led to a tunnel where the ticket station was located. In order to reach the station’s platform, there was a stairway and a long and winding pathway with steep inclines.

Photo 36: Stairs are the only access to the Marshall station. |

The McGregor, Texas station had an inaccessible restroom and a concrete slab with marked accessible spaces on an otherwise gravel parking area. Access from the accessible parking spaces to the station is either across the gravel parking lot or on the irregular brick platform. There is an abrupt level change onto the slab in front of what may be a too narrow entrance door to the station. The station platform was constructed with irregular bricks and there were indications of pooling water.

Photo 37: Irregular brick platform at McGregor station. |

Photo 38: Loose gravel and abrupt level change from parking lot to doorway at McGregor station. |

Vermont

The St. Albans station appeared to have ignored the passage of the ADA. It is an old building with steps to the entrance and no ramp.

Photo 39: St. Albans station. |

The restroom is totally inaccessible and appears to have been unchanged since the 1930s.

Photo 40: Restroom at St. Albans station. |

Virginia

The Ashland station had a step into the station entrance with no ramp, and inaccessible handles on the door and the walkway across the tracks (photo on next page) to the opposite platform is several inches above the platform level with no ramp.

Photo 41: This step at the Ashland station makes the entrance inaccessible. |

The Clifton Forge station was closed when the Virginia P&A visited. There appeared to be no accessible parking spaces in the gravel parking lot, the ramp to the entrance appeared to be too steep and while the station was closed, the restroom was visible from the outside of the station and it clearly lacked grab bars.

The Culpepper station did not have visual train information which was the focus of the visit but otherwise appeared accessible.

Photo 42: This walkway at the Ashland station is inaccessible to wheelchair users and others with mobility-related disabilities. |

The Fredericksburg station was generally confusing and the long ramps did not have level spaces and the visual train information display was not working.

The Lynchburg station in a restored historic building appeared to be accessible.

The Newport News station had deteriorated surfaces in its parking area and did not have visual train information.

The Norfolk station was a temporary station so was not formally surveyed.

The Petersburg station had a deteriorated parking area, had a ramp that appeared too steep and had a difficult to access station door and no accessible ticket counter.

The Richmond Main Street station did not have the closest parking spots assigned as the accessible parking spots, the visual train information equipment was not used, and did not have appropriate signage directing people to the accessible entrance.

The Richmond Staples Mills station had no van accessible parking space, no marked crosswalks, uneven curb cuts, a high threshold for the station entrance door and restrooms stalls that appeared too narrow.

The Staunton station had a narrow doorway with a steep threshold, no visual train information and an inaccessible restroom.

The Williamsburg station did not have a van accessible parking space.

Washington

Photo 43: Deteriorating pavement at the Vancouver station. |

The Ephrata station was closed at the time of the visit, so only the faded parking markings were noted.

The Kelso-Longview station had a visual train information sign that was not operating to provide any information when the loudspeaker system did provide train information.

One of the accessible parking spaces in the Seattle station was measured as having a slightly excessive slope.

The Spokane station had decorative sculptures and an area under an escalator that could present hazards to blind passengers. There was no accessible ticket counter, the ticket area was dark and the restroom door was heavy.

The Vancouver station had deteriorated paving and no van accessible parking. There was no edge protection and deteriorated paving on the East-West platform. There was no accessible portable toilet provided when portable toilets were in use due to a municipal water service interruption. The station visual train information sign was not operating.

Photo 44: No van accessible parking space at the Vancouver station. |

West Virginia

Photo 45: Entrance to tunnel at Harpers Ferry station |

The station building at Harpers Ferry was restored by the National Park Service and appeared accessible so was not surveyed but access between the two platforms is only possible through a tunnel under the tracks served by stairs. There was no ramp or elevator. There also was no sign of a platform lift. This station also serves as a MARC commuter station.

Photo 46: This tunnel is the only way to get from one side of the tracks to the other at Harpers Ferry station. |

Photo 47: Stairs to platform at Harpers Ferry station. |

Appendix A

Michael Montgomery, Former Director, Singing River Industries

In March of 1973, I took the job as director of a work activity center which was a part of the services offered through the local mental health center in Pascagoula, Mississippi. At that time, most Mental Health Centers provided services for people with mental health concerns and people with developmental disabilities. Nearly all had sheltered workshops which were innovative at that time. I, like many directors at the time, had a background in education. I didn’t feel comfortable running a workshop as I did not have the proper educational background or experience. Training provided through the Developmental Disabilities Training Institute in Durham, North Carolina, helped me and others get the training that we needed through a series of five day workshops. It also connected people from various states and offered an opportunity for collaboration.

Our agency was called the Jackson County Training Center. We often received calls from people who wanted to know what kind of training we did. When I arrived, some people with disabilities were doing arts and crafts, but most people were sitting around in a big semi-circle watching the staff do the work. My initial focus was to change from watching staff doing work to getting the people in the workshop to do the work themselves. Over a period of time, I became successful at acquiring contracts for the workshop. We made surveyor stakes for the state highway department and sandblasted rust and old paint from boat trailers, yard furniture, and other metal objects which were prone to rust in our gulf coast climate. Several of our clients (the term widely used at that time) also learned how to apply primer to those surfaces with a spray gun.

In 1976, I was introduced to the work of Dr. Marc Gold. Marc helped me understand that we could teach really sophisticated skills by using systematic instruction. I began to see that we should not be only providing segregated activities. Rather than keeping people in the workshops, we needed to get people out of sheltered workshops into jobs in the community. I was open to what Marc had to say because I could see, even in 1974 and 1975, that there would be an endless line of people coming to us from voc rehab and the schools. It was my impression at the time, that VR referred about 90% of the people with disabilities that came to them to sheltered workshops. VR would verify them as unemployable, refer them to workshops for work activity, and we would be the end of the line for them. VR’s traditional testing and evaluation procedures did not support the notion that those individuals could perform real work. I was also open because I could see that we could train people to do what others were doing in the community, but they would never get the opportunity without some assistance.

After meeting and working with Marc, we secured funding through United Way to hire someone to slowly move people from the workshop into community jobs. We found that people could work, if someone was willing to negotiate on behalf of people with disabilities and work with the employers to accommodate individual disabilities. If we trained correctly, and not tested, we could find the right match for people’s abilities. We were very successful in getting people out of the workshop and into employment in the community.

We had a subcontract with Macmillan Bloedel to make cedar boards for privacy fencing. The plant manager was Joel Donovan. Rather than building the fences in our workshop and paying for materials to be moved back and forth, our crew went to his location. Our people liked working with the other workers, liked being seen and respected. On days when there was no work, the individuals on that subcontract would come back to shop until their services were needed again. On those days, some of them would stay home or come under pressure from their families. They clearly didn’t want to come back. They had graduated from the workshop. I understood and respected their position.

We got people jobs in hospitals, restaurants, and other businesses around the community. One of the people that we trained in the late 1970s worked in a local hospital until his recent retirement. TS came to us straight from an institution, where he had lived from early childhood until his 20’s. Like so many people at that time, he never should have been at the institution. TS ran our sandblaster, drove our forklift; it was clear that he could do more. His job started in the hospital laundry, but he moved all around the hospital. He was a good worker. We made ourselves available to the hospital administration; if they had a problem with TS’s skills, they could call us, and we would provide additional training. Over the years, the hospital did call us a few times, and we were able to provide the training that was needed. TS was absorbed into the fabric of the community. After he got the job, TS got his own apartment and started dating a woman that he met in the workshop. He didn’t have a driver license, but he used his bicycle to get around.

Our ideas sometimes scared families. They had been told by doctors and service systems that their kids needed to be in a sheltered and safe environment. Although some of the parents of children in the workshop began to realize that their son or daughter could do good work, it was the switching of environments that was troubling. One of our parents who at the time was very concerned that his son stay in the safe environment of the workshop, recently told me that his son was working in a restaurant where he was very happy. He could now see the benefits of working in the community. His son enjoyed being viewed as a regular employee, but for fewer than 40 hours. Families need assurance that their children will have a meaningful job and not spend part of their time at home alone. The Community Calendar developed by Marc Gold and Associates is a tool that we used to develop a life in the community around work and non-work time.

In the 1970’s, the sheltered workshops in Mississippi were run by annually renewable grants. In the 1990’s, the funding was converted to a purchase of service arrangement for X dollars per unit of service. People who ran the programs were not motivated to change. They liked the way that the billing flowed and the families were happy to have their children in a safe place and were not pushing for change. Folks believed then, and I think that many still do, that people need to be sheltered. They just don’t believe that people can grow with the right training and support, that they can have a good life. I believed that we owed it to each individual and family to try new ideas and work diligently for each person regardless of disability. If we failed to put our heart and soul into the challenge for everyone, we would never see their potential. Everyone that I have ever worked with truly wants a life with work, a place to live, friends, and social outings. A job provides the money to secure everything else.

There are more than 1,800 people on our waiver waiting list in Mississippi alone. Many could come off the waiting list if we switched the way we use our resources. It saddens me that it is taking so long for this switch to occur, but I do now our state leaders move toward the change through a re-balancing initiative.

Michael Montgomery is the former Director of Singing River Industries, a sheltered workshop in Mississippi. He is currently a member of the Board of Directors of Disability Rights Mississippi.

Appendix B

|

||||||||||||||

Appendix C

Section 14(c) Certificates[1] and Sheltered Workshops[2] by State

| State | Total Served | % | % Community- Based Non work | % | Total Section 14(c) Certificates |

| Integrated Employment | Combined Facility-Based Settings | ||||

| AK | 1,394 | 24% | 54.5% | 8 | |

| AL | 5,269 | 5% | 0% | 95% | 56 |

| AR | 65 | ||||

| AZ | 41 | ||||

| CA | 78,250 | 11% | 74% | 15% | 238 |

| CO | 5,731 | 27% | 59% | 62% | 42 |

| CT | 8,433 | 56% | 44% | 9% | 70 |

| DC | 1,449 | 7% | 10% | 78% | 1 |

| DE | 1,546 | 26% | 1% | 68% | 6 |

| FL | 18,692 | 23% | 27% | 58% | 102 |

| GA | 98 | ||||

| HI | 2,865 | 4% | 98% | 56% | 8 |

| IA | 82 | ||||

| ID | 6,980 | 5% | 30% | 58% | 14 |

| IL | 25,500 | 10% | 0% | 94% | 180 |

| IN | 12,491 | 25% | 12.5% | 62% | 63 |

| KS | 5,991 | 19% | 54% | 80% | 60 |

| KY | 7,975 | 17% | 29% | 54% | 55 |

| LA | 4,139 | 34% | 2% | 64% | 95 |

| MA | 14,038 | 22% | 12% | 65% | 88 |

| MD | 9,768 | 38% | 0% | 62% | 48 |

| ME | 4,133 | 19% | 77% | 0% | 21 |

| MI | 81 | ||||

| MN | 149 | ||||

| MO | 4,030 | 9% | 2% | 94% | 120 |

| State | Total Served | % | %

Community- Based Non work |

% | Total Section 14(c) Certificates |

| Integrated Employment | Combined Facility-Based Settings | ||||

| MS | 5,904 | 7% | 70.5% | 40% | 28 |

| MT | 32 | ||||

| NC | 100 | ||||

| ND | 1,782 | 22 | |||

| NE | 3,668 | 33% | 0% | 77% | 39 |

| NH | 2,159 | 45% | 49% | 5% | 10 |

| NJ | 9,081 | 15% | 5% | 80% | 74 |

| NM | 3,056 | 32% | 31% | 65% | 8 |

| NV | 1,919 | 20% | 2.5% | 77% | 15 |

| NY | 55,420 | 15% | 67% | 32% | 153 |

| OH | 32,133 | 23% | 4% | 66% | 163 |

| OK | 4,168 | 61% | 30.5% | 53% | 78 |

| OR | 3,834 | 5% | 10.5% | 67% | 68 |

| PA | 139 | ||||

| RI | 12 | ||||

| SC | 7,549 | 30% | 0% | 83% | 80 |

| SD | 2,307 | 24% | 24% | 100% | 34 |

| TN | 7,770 | 22% | 79 | ||

| TX | 40,038 | 9% | 28% | 46.5% | 165 |

| UT | 2,670 | 33% | 72% | 0% | 42 |

| VA | 11,259 | 21% | 2.5% | 79% | 67 |

| VT | 2,252 | 39% | 61% | 0% | 2 |

| WA | 7,183 | 57% | 4% | 11% | 58 |

| WI | 10,338 | 33% | 143 | ||

| WV | 21 | ||||

| WY | 1,216 | 20% | 15% | 65% | 12 |

| 430,247 | 24% | 27% | 58% | 3,435 |

[1] Data retrieved by Congressional Research Service from Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor, Current as of January 5, 2010

[2] Institute for Community Inclusion, StateData: The National Report on Employment Services and Outcomes (2008).