Despite the fact that the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 requires all polling places to be accessible to people with disabilities and the Help America Vote Act of 2002 mandates that all Americans have the right to a private and independent vote, polling places and voting stations across the U.S. remain largely inaccessible.

In this report, Blocking the Ballot Box: Ending Misuse of the ADA to Close Polling Places, the National Disability Rights Network spoke to and visited counties with recent Department of Justice settlements for polling place accessibility. NDRN’s recommendations and suggestions are available in the conclusion section of this report.

Go to Press Release

Download “Blocking the Ballot Box” (Word)

Download “Blocking the Ballot Box” (PDF)

Download “Polling Place Accessibility: The Recommendations” (PDF)

Download “Federal Law and Voter Access: The Breakdown” (PDF)

The National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) wishes to thank the Ford Foundation and the Democracy Fund for their financial support of this project to explore the alarming trend of polling places closures blamed on people with disabilities and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

NDRN would also like to give a special thank you to JJ Rico and Renaldo Fowler of the Arizona Center for Disability Law and Therese Yanan of the Native American Disability Law Center for going above and beyond, traveling miles upon miles with NDRN staff to showcase what Native American voters with disabilities experience in the Four Corners region of the United States. Thank you to Coconino County’s Elections staff who spent the day with NDRN staff exploring the unique challenges their county experiences on Election Day.

NDRN also wants to express our deepest gratitude to community leaders of the Navajo Nation and Hopi Tribe who welcomed us with open arms in their community and shared the challenges they face while voting.

There would be no report without the time and input from elections administrators, voting rights experts, and disability rights advocates across the country, including:

- Adam Lasker, Association of Election Commission Officials of Illinois

- Alexander Castillo-Nunez, Inter Tribal Council of Arizona

- Barry Stephenson, Jefferson County, Alabama Government

- Barry Taylor, Equip for Equality

- Bebe Novich, Equip for Equality

- Berna Chavez, Disability Rights New Mexico

- Christian Adcock, Disability Rights Arkansas

- Gabe Labella, Disability Rights Pennsylvania

- John Cusick, NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

- Julie Kegley, Georgia Advocacy Office

- Katy Smith, Anderson County, South Carolina Government

- Leah Aden, NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

- Leigh Chapman, Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

- Maggie Knowles, Protection & Advocacy for People with Disabilities, Inc.

- Molly Broadway, Disability Rights Texas

- Nevada Disability Advocacy and Law Center

- Scott Simpson, Muslim Advocates

- Sharon Woodard, York County, South Carolina Government

- Shirley Walker-McKinnis, Disability Rights Mississippi

- Sophia Lin Lakin, American Civil Liberties Union

- Stephanie Patrick, Disability Rights Center – New Hampshire

- Stephanie West-Potter, Disability Rights Center of Kansas

- Tate Fall, Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program

- Tom Masseau, Disability Rights Arkansas

- Torey Dolan, Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

- Wanda Hemphill, York County, South Carolina Government

This report was researched and written by Erika Hudson and Michelle Bishop of the National Disability Rights Network. Curtis Decker, David Hutt, Eric Buehlmann, Tina Pinedo, Kenneth Shiotani and David Card edited the report.

Production was coordinated by Tina Pinedo and David Card.

The National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) is the nonprofit membership organization for the federally mandated Protection and Advocacy (P&A) Systems and the Client Assistance Programs (CAP) for individuals with disabilities. The P&As and CAPs were established by the United States Congress to protect the rights of people with disabilities and their families through legal support, advocacy, referral, and education. P&As and CAPs are in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. territories (American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and there is a P&A and CAP affiliated with the American Indian Consortium which includes the Hopi, Navajo, and San Juan Southern Paiute Nations in the Four Corners region of the U.S.

As the national membership association for the P&A/CAP network, NDRN has aggressively sought federal support for advocacy on behalf of people with disabilities, and expanded P&A programs from a narrow initial focus on the institutional care provided to people with intellectual disabilities in facilities to include advocacy services for all people with disabilities no matter the type or nature of their disability and where they live. Collectively, the P&A and CAP Network is the largest provider of legally based advocacy services to people with disabilities in the United States.

Today P&As and CAPs work to improve the lives of people with disabilities by guarding against abuse; advocating for basic rights; and ensuring access and accountability in health care, education, employment, housing, transportation, voting, and within the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Through the Protection and Advocacy for Voter Access program, created by the Help America Vote Act, the P&As have a federal mandate to “ensure the full participation in the electoral process for individuals with disabilities, including registering to vote, casting a vote and accessing polling places” and are the leading experts on access to the vote for people with disabilities in the U.S.1

If you live in the United States, what are your rights? To this question, many of us might say the right to free speech, the right to petition government, the right to a free press, and the right to assemble. Or perhaps you would say the right to vote – the foundation of our democracy, the right on which all of these other rights depend.

As we have worked toward a more perfect union, the right to vote has evolved. The Fifteenth, Nineteenth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments to the United States Constitution have expanded the franchise, as legislation like the Voting Rights Act and the Help America Vote Act were passed to protect it. Today, although we have come so far over the course of our history, our electoral system far from perfect.

Voters across the country are still being denied equal access to the ballot box and this includes voters with disabilities. Laws, such as the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act, are in place to protect the rights of people with disabilities and their access to the vote. Yet jurisdictions make routine decisions every election cycle, knowingly or unknowingly, that prevent equal access on Election Day. Americans have fought too long and too hard to create a representative government in which everyone has a voice and a vote. We must do better.

This means that we must stop blaming people with disabilities and the laws that protect their rights. Over the course of recent elections, we have heard of counties and cities closing, relocating, or consolidating their polling places while unjustly invoking the historic civil rights provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Many of these same jurisdictions have lamented being “targeted” by the U.S. Department of Justice when it rightly steps in to enforce federal disability rights law and to ensure equal access at polling places across the country.

The narrative simply cannot be to blame people with disabilities for, in fact, being victims of widespread failure to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Instead, we must come together with dignity and respect to ensure all eligible voters the same opportunity to a private and independent vote. This change will not be easy. People with disabilities know this all too well, as proven by years of unequal access and denial of their civil rights, but it must happen.

People with disabilities have overcome tremendous odds to participate in elections, but they simply should not have to. People with disabilities will continue to have their voices heard on Election Day. They are a force in American politics. They cannot and will not be scared off from the ballot box as the U.S. strives for full realization of equal access.

Sincerely,

Curtis L. Decker, J.D.

Executive Director

America’s electoral system is complex, extremely localized, and operates in an environment of unrealistic expectations of perfection. Although voting laws in the United States have changed over time and advanced access for all voters, the nation still has a long way to go in order to ensure that all Americans have equal access to the vote. Throughout history, Black voters, low-income voters, women voters, Native American voters have not always had their right to vote protected, and even now well into the 21st century. America still struggles to ensure equal access to the ballot box.

People with disabilities crosscut every American demographic, and voters with disabilities are a part of every voting bloc in society. Yet, voters with disabilities have also been restricted from the vote throughout history, which continues today. People with disabilities face significant barriers when participating in U.S. elections, preventing equal access to the vote. Despite the fact that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 requires all polling places to be accessible to people with disabilities and the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002 mandates that all Americans have the right to a private and independent vote, polling places and voting stations across the U.S. remain largely inaccessible.

National and state-based surveys have shown time and time again that America’s polling places have long been inaccessible to voters with disabilities. The United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2016 found that 40 percent of U.S. polling places were accessible during that year’s November election. With 40 percent representing an all-time high for polling place accessibility, less than half of America’s polling places were accessible during a presidential election. The GAO, as well as surveys conducted in states like South Carolina, Arkansas, Texas, and Vermont, have found these barriers include unpaved parking, unsafe sidewalks, and inaccessible entrances, hallways, and voting areas. Despite the fact that people with disabilities face barriers to the ballot box, they are alarmingly also being blamed for preventing others from voting as well.

When the United States Supreme Court struck down key provisions of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 in Shelby County v Holder in 2013, it allowed jurisdictions with a demonstrated history of discriminatory voting practices to change freely how their elections are administered without the voter protections offered by federal preclearance. Voters across the country were, and still are, negatively impacted by new barriers created after the Shelby County decision. Following the enactment of strict voter identification laws, voter purges, and polling place closures, not all voices are being heard on Election Day, and worse, they are being deliberately silenced.

Local jurisdictions in various states have gotten away with blaming their polling places closures on the access needs of voters with disabilities. The closures effectively suppress the vote in those jurisdictions and create a national environment of fear among voting rights activists. A false narrative that the federal government is encouraging jurisdictions to close polling places if they are not accessible under the law leaves disability rights activists hard-pressed to advocate for poll access.

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ) has been tasked with enforcing the ADA since its passage, and as a result, have intervened in many jurisdictions that are out of compliance with the ADA. DOJ intervention typically results in a settlement agreement that mandates ADA- compliance through any number of measures, including temporary accessibility modifications or measured relocation of polling places to more accessible locations. The DOJ also cautions jurisdictions against closing polling places in their enforcement of the ADA. Overwhelmingly, jurisdictions that experienced DOJ intervention followed the Department’s recommendations to make their polling places more accessible in cost-effective ways, while preventing unnecessary poll closures. Meanwhile, jurisdictions that attempted to close a significant percentage of their polling places and cited the ADA typically were not under a settlement agreement with the DOJ. These jurisdictions failed to provide ADA accessibility surveys or any evidence of coordination with disability advocacy organizations to resolve access barriers.

Jurisdictions like the City of Chicago, Illinois and Coconino County, Arizona have made headlines for their recent DOJ settlement agreements and for their efforts to comply with the ADA. Chicago, a diverse area with a large number of polling places; and Coconino County, the second largest county by area in the nation consisting largely of Native American Sovereign Nations, have made their best efforts to ensure voters have equal access to polling places. The settlement agreements with these jurisdictions, however, have been called into question by voting rights activists and the media even while doing their best to ensure that all voters have equal access to polling places in their home communities.

The disability community does not encourage polling place closures. Rather, disability rights activists encourage communities to work together to provide permanent or temporary fixes to polling places. Disability rights organizations at the state and national level spoke out against the aborted plan to close polling places in Randolph County. Disability rights activists recognize that poll closures hinder access for all voters, including those with disabilities. The solution to inaccessible polling places is not to close them…it is to make them accessible. Further, the cost of making polling places accessible can perhaps be much cheaper than arguing against it in court.

Many creative solutions already exist to ensure access. Many polling places can be permanently or temporarily modified at little to no cost. Reasonably accessible locations may only require changing the path of travel or utilizing a more accessible area in the same location. In some cases, polling places may need to be relocated or consolidated with another polling place in the immediate area in order to achieve access. Finding the best solution, and keeping polling places open, relies on including people with disabilities in the planning process, combining elections official’s expertise in administering elections with disability advocate’s expertise in providing access.

It is evident that none of this happened in Randolph County and in many other areas across the country, resulting in attempted localized voter suppression, as well as national confusion and finger pointing. Jurisdictions under DOJ intervention are often eager to do the right thing and comply with federal accessibility law. To do so, election officials must increase their capacity by tapping into the local disability community and their expertise in the access needs of voters with disabilities. Conversely, jurisdictions leveraging disability rights law to close large numbers of polling places with little to no evidence of the closures’ necessity must be prevented from suppressing voter participation. Federal preclearance under the VRA has proved an effective vehicle for deterring these kinds of discriminatory practices and must be fully restored. Other recommendations and suggestions are available in the conclusion section of this report.

This research analyzes whether jurisdictions are using the ADA as a pretext to close polling places across the country and the role of the U.S. DOJ, which is tasked with enforcing the ADA. The analysis relied on polling place accessibility surveys completed and aggregated by Protection and Advocacy (P&A) systems, U.S. Government Accountability Office surveys of polling place accessibility across the country dating to 2000, data on polling place usage from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC)’s Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), and the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Right’s Democracy Diverted: Polling Place Closures and the Right to Vote report, and public settlement agreements on ADA-compliance of polling places with the DOJ under the Department’s ADA Voting Initiative and Project Civic Access Initiative.

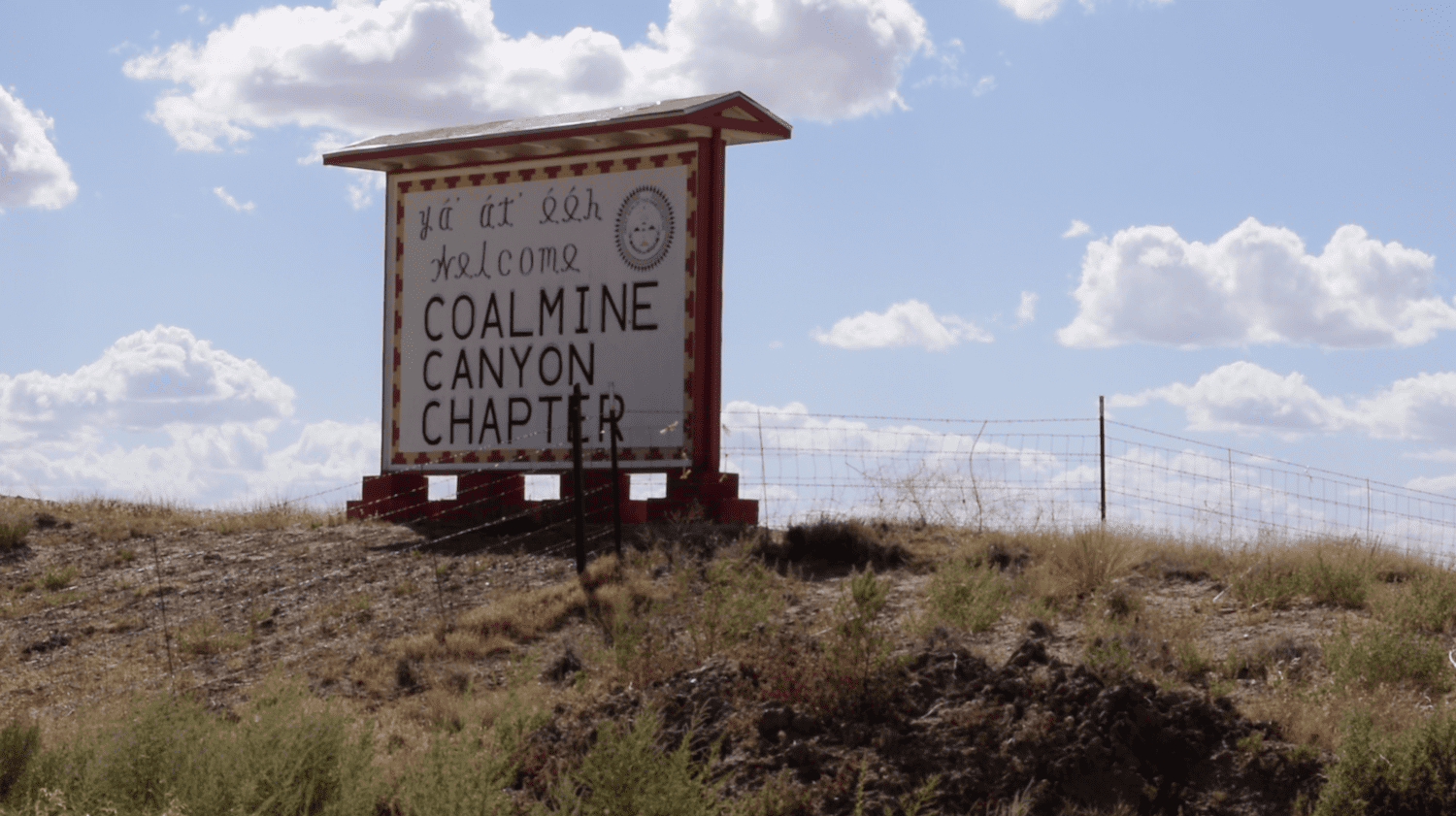

Interviews were also conducted with P&A staff and local election officials in reviewed jurisdictions to collect qualitative data on the barriers faced by voters and election administrators on Election Day and beyond. NDRN staff traveled to Coconino County, Arizona in September 2019 to interview elections staff, community and tribal leaders and to examine several polling places first-hand, including Cameron’s Senior Center, Tuba City High School, Moenkopi Community Center, and Coalmine Chapter House.

VRA – Voting Rights Act of 1965

VAEHA – Voting Accessibility for Elderly and Handicapped Act of 1984

ADA – Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

NVRA – National Voter Registration Act of 1993

HAVA – Help America Vote Act of 2002

ADAAG – ADA Accessibility Guidelines

P&A – Protection and Advocacy

CAP – Client Assistance Program

PAVA – Protection and Advocacy for Voter Access

DOJ – Department of Justice

FY – Fiscal Year

GAO – Government Accounting Office

EAC – Election Assistance Commission

DRDC – Disability Rights DC

DRTx – Disability Rights Texas

DRA – Disability Rights Arkansas

DRVT – Disability Rights Vermont

ASL – American Sign Language

In August 2018, Randolph County, a majority black county in rural Georgia, made national news for proposing to close seven out of its nine polling places ahead of a highly contested November gubernatorial election. The reason given – a landmark civil rights law, the ADA.

Signed in 1990, the ADA is the major civil rights law in the United States that protects the rights of people with disabilities. The ADA outlawed disability-based discrimination, in employment and public programs, and granted equal access to public goods and services for people with disabilities. Specifically, Title II of the Act mandates that people with disabilities must be given full and equal opportunity to vote by federal, state, and local governments. In other words, the ADA requires counties and cities in the U.S. to select and use polling places that are physically accessible to everyone, including “people with a variety of disabilities, such as those who use wheelchairs, scooters or other devices; those who have difficulty walking or using stairs; or those who are blind or have vision loss.”2

The U.S. Census Bureau reported in 2010 that 56.7 million people with disabilities live in the United States, totaling approximately 19 percent of the U.S. non-institutionalized population.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention4 and Pew Research Center5 believe that number is now closer to 25 percent, or one in four Americans. Further, the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers University projected that there were 35.4 million people with disabilities eligible to vote in the U.S., one-sixth of the total American electorate, during the 2016 Election.6

The size of the disability community and the magnitude of the ADA and its positive impact on civil rights and American life simply cannot be overstated. The ADA is the standard in enforcing access to the ballot for eligible voters with disabilities, protecting their voice in democracy.

A number of counties that have attempted to shutter a high percentage of polling places in the last several election cycles cite failure to follow Title II of the ADA, which may be true. In fact, given the Government Accountability Office’s data on the pervasive nationwide failure to comply with the ADA in elections administration – it is very likely true. However, the ADA does not mandate closure of inaccessible polling places in its provisions. In fact, DOJ explicitly cautions against closing polling places in their enforcement of the ADA. Similarly, disability advocates in the U.S. do not suggest closing polling places to resolve ADA violations.

Unfortunately, what happened in Randolph County was not an isolated incident. Multiple jurisdictions have flown largely under the radar in citing the ADA as the reason for closing, relocating, and consolidating their polling places. Some jurisdictions say they have no choice but to close or relocate. Anecdotally, some jurisdictions do not think they are doing anything wrong alleging that no people with disabilities live in their community and therefore they do not need to follow the ADA. Still, some jurisdictions do not even know they are violating the law, claiming confusion over the ADA’s provision and its interaction with state laws. For elections officials with limited in-house capacity, the ADA is often seen as a burden to those who do not benefit from its protections every day. The work of disability rights advocates and federal enforcement are necessary to combat persistent ignorance and confusion surrounding the ADA and ensure equal access for every American.

Most water fountains today, or “bubblers” as some like to say, look standard. They are mounted on walls at about waist level and most people have to bend down to take a sip of water, or perhaps lift children up so they can take a sip on a nice hot summer day. Some drinking fountains even have those updated reusable bottle refill stations for easy access. That is to say, water fountains have evolved over the years. In the past, water fountains were connected to the ground, instead of mounted on the wall. The “floating” redesign seen today is actually what makes them accessible to wheelchair users, who are then able to roll underneath to reach the spout. Yet, the same drinking fountains that once were not accessible to wheelchair users have created a new kind of barrier, they cannot always be detected by a white cane sweeping across the ground so that people who are blind or visually impaired can navigate around them.

Veritably, the solution that provided access for one person with a disability created a dangerous accessibility barrier for another. The disability community is large and diverse, and each type of disability differs from the next and invites a unique set of access barriers to be toppled. Yet with a little innovation and commitment to good design, the same bubbler can be made accessible for all. Water fountains ideally are mounted on the wall with open clearance underneath to accommodate wheelchairs, but placed within a small alcove carved out of the wall so that the fountain is no longer blocking a path of travel and does not need to be cane detectable. The solution was not to close the water fountain and force all thirsty citizens to travel great distances to the next available bubbler. The solution was not to allow non-disabled drinkers to access the fountain, while expecting people with disabilities to drink at home or wait for a pitcher to be brought outside.

This is not to say that water fountains are at the core of the problems facing today’s voters. However, much like the trusty water fountain, electoral systems have been re-designed continually to promote access to the vote for all…and somehow have managed to largely leave many voters with disabilities behind.

The solution was to take something that should have been accessible to everyone all along and re-envision it to be so.

For decades during American history, literacy tests, poll taxes, and other voter suppression tactics have restricted and prohibited the right to vote. More recently, polling place closures, strict photo identification laws, and purging of voter rolls have emerged as threats to the core of our democracy and have prevented voters from participating in their electoral system. Yet, Constitutional amendments and passage of sweeping voting rights laws have continually combatted barriers to the ballot box as they arise. People with disabilities have been impacted by every Constitutional amendment and piece of legislation related to voting, as disability lies within every community.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 prohibits known discriminatory practices, including literacy tests, and established federal preclearance as a proactive measure to prevent voter suppression. A historic achievement for the civil rights movement, the VRA is also likely the oldest legislation of its kind to include provisions for people with disabilities. Section 208 of the VRA provides that “any voter who requires assistance to vote by reason of blindness, disability, or inability to read or write may be given assistance by a person of the voter’s choice, other than the voter’s employer or agent of that employer or officer or agent of the voter’s union.”7

Section 5 of the VRA mandates that counties and cities with a history of discrimination report any changes in election administration to the DOJ and the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia prior to making any changes, including closing or relocating polling places. Section 4 of the VRA includes a formula to determine which states or jurisdictions will be subject to federal preclearance. To many, federal preclearance under the VRA was an invaluable tool to ensure discrimination was stopped before it began.

The Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act of 1984

Prior to 1984, polling places were not required to be physically accessible for people with disabilities or required to accommodate people with disabilities, even if it meant they could not vote because of it. However, when Congress passed the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act (VAEHA) in 1984, states were required to ensure accessible polling places during federal elections. The VAEHA sought to give people with disabilities the right to equal access to polling places six years before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act.8

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

Although some improvements to polling place access were required by prior voting rights legislation, the ADA was the landmark civil rights legislation for people with disabilities, which includes provisions for voting.9 While the VAEHA allowed for alternative means to vote when those with disabilities were assigned to an inaccessible polling place, Title II of the ADA requires state and local governments to ensure that people with disabilities have a full and equal opportunity to vote. The ADA was the first piece of major legislation to require the equal treatment of people with disabilities by society. As George H.W. Bush famously stated when signing the ADA in 1990, “Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.”10

ADA-Compliance at Polling Places

According to the DOJ, the five most common ADA violations at polling places over recent years include: 1.) Parking 2.) Sidewalks 3.) Entrances 4.) Hallways and 5.) The voting area itself.11 Understandably, these violations can be somewhat complicated. For example, simply paving a sloped parking lot or building a ramp that is too steep or not wide enough will not provide access. Public and private entities need to consider all elements of accessibility, including slopes, grades, and distances to make curb cuts, sidewalks, parking lots, passenger drop off areas, and other paths of travel usable and safe. In other words, the most well intended paved parking lots, ramps, or other accessibility changes can still be inaccessible if not in compliance with the ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG).12

PARKING

In order to ensure ADA-compliance of parking lots, election officials must refer to precise measurements and collect accurate data. The ADA provides requirements for access aisles – those areas where cars do not park and that allow enough space for an accessible vehicle’s ramp or lift to deploy for wheelchair access. Under the ADA, access aisles must be at least 60 inches wide for cars and 96 inches wide for vans. Access aisles typically feature diagonally striped lines or some way to indicate “no parking.” In addition, while a jurisdiction looking to affordably bring an unpaved parking lot into compliance may opt to pave only the accessible parking space, the parking space and access aisle itself must not have a significant slope and must be level with the rest of the parking area to prevent a wheelchair from falling backwards off the paved accessible space.

An accessible parking spot at a polling site in Virginia City, located in Storey County, Nevada. Photo courtesy of Nevada Disability Advocacy and Law Center.

All accessible parking spaces must include signs to ensure full ADA-compliance. A sign designating the accessible space for people with disabilities must be placed by every individual accessible parking space so that every driver knows the space can only be used by those with accessible parking license plates or tags, as determined by the state.

SIDEWALKS

Safe sidewalks are crucial for voters with disabilities to have equal access to their polling places. Sidewalks must be at least 36 inches wide and must not have level changes greater than half an inch. They also need to be maintained and repaired when needed. Good sidewalks make things easier for everyone. Not only do those who use wheelchairs, walkers, and canes greatly benefit from safe sidewalks, but those with strollers, or people with temporary disabilities (such as a cast and crutches for a broken leg) use them as well. It is required that curb ramps (curb cuts), the ramps that enable access on and off of sidewalks, not be too steep. Curb ramps are dangerous if they are too steep or lack flared sides and could in fact force a person with a disability into oncoming traffic if the ramp cannot be traversed successfully.

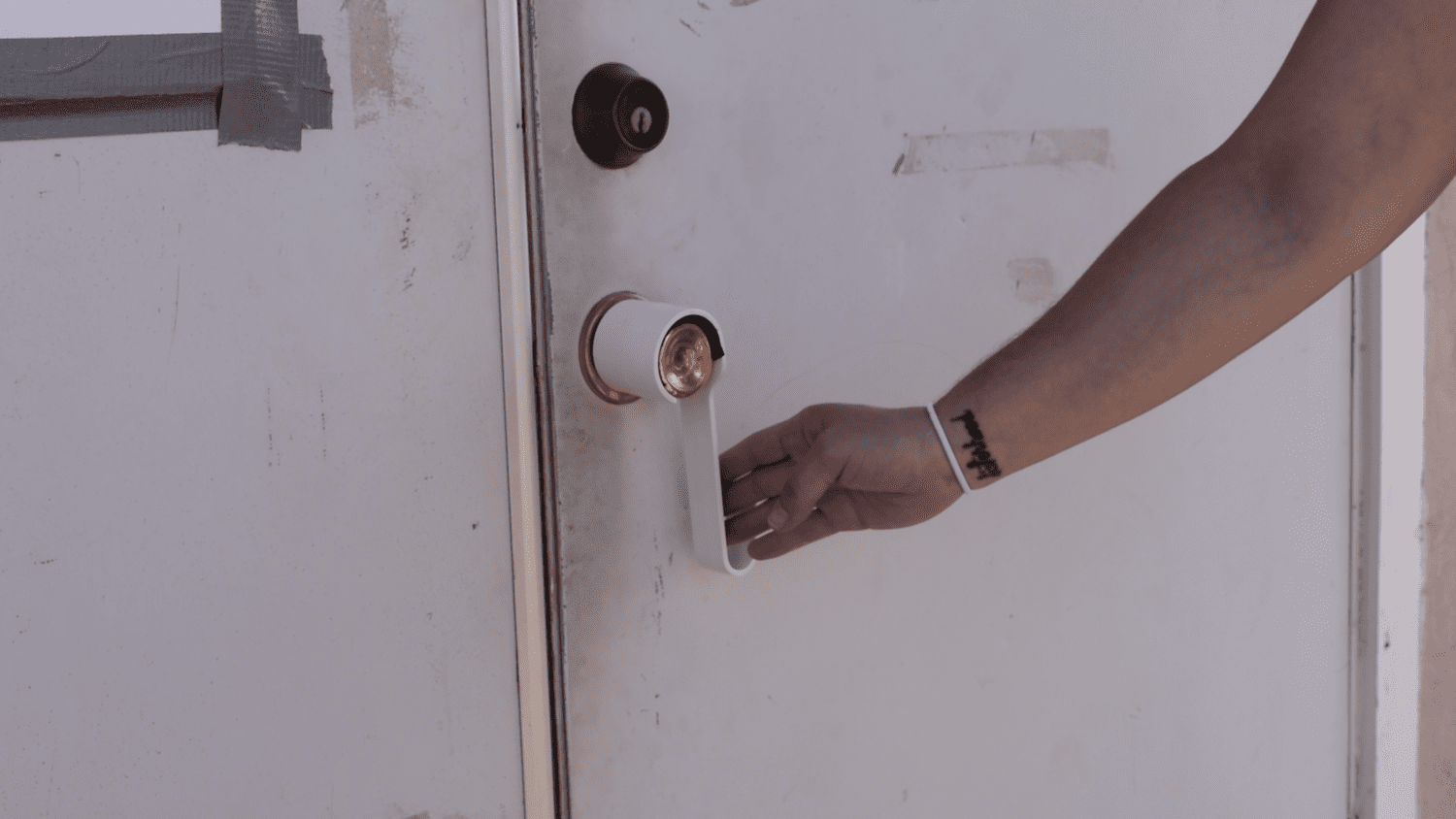

ENTRANCES

Polling place entrances must be ADA accessible as well to ensure equal access. No voter’s ability to access the ballot should depend on the kindness of strangers to hold a door open for a voter with a disability. All door openings must provide at least 32 inches clear width, and the door threshold should not exceed a half an inch in height and be beveled if more than one-quarter inch in height. As with parking and sidewalks, entrance areas must be level and should not slope steeply in any one direction. For example, a wheelchair user must be able to open the door with enough space to back up or maneuver and provide space for the door’s swing without being hit by the door, blocked from the doors opening, or rolling backwards. Additionally, the door handle itself must not require tight grasping, pinching, or twisting – such as a round knob. Rather, lever type door handles, which are operable with a closed fist, provide access to most people.

HALLWAYS

Hallways at polling places must provide an accessible route of at least 36 inches clear width. Hallways should not have any objects protruding the path of travel to the voting area itself at a polling place in order to accommodate different types of mobility devices, like wheelchairs. For example, wall-mounted objects such as water fountains should be mounted inside an alcove in the wall that prevents any protrusion. Otherwise, water fountains or other objects cannot extend more than 4 inches from the wall and cannot reduce the clear route and also should be detectable by a white cane used by those who are blind to navigate a path.

VOTING AREA

The voting area itself (i.e. start to finish path of travel from entering the area, to voting stations, to exiting the polling place) must provide an accessible route that is at least 36 inches wide. The floor surfaces in the voting area must also be flat and stable. Power cords for accessible voting and other devices must be covered or taped down to prevent tripping.

The National Voter Registration Act of 1993

The National Voter Registration Act (NVRA or Motor Voter Act) of 1993 made it easier for Americans to register to vote, including people with disabilities. For example, the Act requires states to offer voter registration opportunities at offices that provide public assistance and services to people with disabilities, such as Vocational Rehabilitation services and Independent Living Services.13

The Help America Vote Act of 2002

In 2002, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) with the goal to reform the voting process throughout the country and make it easier for all Americans to participate in democracy. HAVA mandates that voters with disabilities have the same opportunity to vote “privately and independently” by requiring that every polling place have at least one voting system that is accessible to people with disabilities.14 Accessible voting systems are typically either a direct recording electronic (DRE) voting system, which uses an electronic interface to cast and record votes electronically with or without a paper back up, or ballot marking devices (BMDs), that use an electronic interface to assist voters to mark selections on a paper ballot that is then cast.15

HAVA also established the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) as an independent, bipartisan federal commission to develop guidance and act as a clearinghouse of best practices to meet HAVA’s requirements, including access for voters with disabilities. Additionally, HAVA created the PAVA program as a direct charge to P&As to assist in HAVA’s implementation and ensure voter access for people with disabilities from registration to casting a ballot. PAVA is the first dedicated source of funding for advocacy for voters with disabilities.

Despite laws to protect people with disabilities’ right to vote by mandating public entities, such as polling places, be accessible — jurisdictions consistently fall short on delivering equal access to people with disabilities.

Physical Access to Polling Places

Polling place closure is not appropriate, but it is important to acknowledge that many polling places are still not accessible to people with disabilities, despite over 30 years of the VAEHA and ADA. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO)16 and the P&A Systems, the nation’s largest providers of legal advocacy services for people with disabilities, have published numerous reports over the years highlighting the many barriers that still face people with disabilities while voting.

Across the United States

The GAO has issued congressionally requested reports dating back to 2000, immediately before the enactment of HAVA, creating arguably the most comprehensive record of the lack of ADA-compliance in America’s polling places. GAO’s most recent report following the 2016 presidential election surveyed 178 polling places across the country, of which 107 of those polling places posed barriers to voters with disabilities.17

According to the GAO’s report, 28 of the 178 polling places had ADA violations related to parking. Fifty-eight polling places had issues related to the path of travel up to the entrance of the polling place, and 39 polling places alone had inaccessible building entrances. Thirty-five of the polling places had barriers related to the path of travel to the voting area, while inside the polling place. Furthermore, of the 178 polling places, the GAO was able to examine 137 voting stations and found that 89 of them violated HAVA and the ADA by not providing an accessible voting system that was ready for use and allowed for a private and independent vote.18

South Carolina

In October 2018, Protection and Advocacy for People with Disabilities Inc., South Carolina’s P&A, issued a report on polling place accessibility. They surveyed a total of 32 polling places and found that all 32 of the polling places they surveyed violated either VAEHA, the ADA, and/or HAVA.19 P&A staff and volunteers discovered inaccessible parking, walkways, and entrances, as well as inaccessible voting machines and a lack of ramps.

The P&A issued key recommendations to prevent inaccessible polling places in future elections. Their main recommendation was training; election officials must understand the various disability rights laws and how to implement them properly. Many of the problems discovered by the P&A could be eliminated with proper training to election officials and poll workers, not requiring closures of the polling places.20

District of Columbia

During the June 2018 primary election, Disability Rights DC (DRDC), the District of Colombia’s P&A, surveyed 121 polling places in the District. DRDC reported that 14 percent of the polling places they surveyed were structurally inaccessible while 34 percent of the polling places were operationally inaccessible. In the report, structurally inaccessible refers to obstructed paths to voting areas, lack of accessible entrances, and inaccessible ramps and elevators. Operationally inaccessible meant lack of signage, closed doors, malfunctioning doorbells, and lack of available poll workers.21

Arkansas

From October 2017 to July 2018, Disability Rights Arkansas (DRA), Arkansas’s P&A, surveyed polling places in each of the state’s counties. DRA was able to survey 90 percent of the state’s polling places and found that 49 percent of them were inaccessible to people with disabilities.22Their survey findings noted that parking was the most common violation, with 866 out of the total 1,110 polling places having accessibility violations in parking.23

DRA also noted in their report that 490 of the state’s polling places at the time were owned by churches or religious organizations. Churches and religious institutions are one of the few places where people gather that are not covered by the ADA. However, all polling places are subject to ADA regulations, whether or not they are being housed at a facility with a religious affiliation. Thus, the onus is placed on the jurisdiction’s election officials to ensure that the polling place is at least temporarily accessible under the ADA when the facility is being used as a polling site.24

Four Corners Region

The Native American Disability Law Center, the American Indian Consortium’s P&A, is located in the four corners region of the U.S. — covering parts of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. In 2013, the Law Center issued a report entitled The Fundamental Principal of a Participatory Democracy: Equal Access for Navajos with Disabilities.25 The Law Center staff and volunteers surveyed 25 polling sites in five major communities across the Navajo Nation that host tribal, state, county, and federal elections and found that every single polling place they surveyed had barriers to people with disabilities. These barriers included unpaved parking lots, inaccessible door handles, and limited accessible signage.26

Texas

Disability Rights Texas (DRTx), the Texas P&A, conducts regular polling place accessibility checks and offers their services free of charge to county election officials to ensure that their polling places are ADA-compliant before Election Day. On June 25, 2019, DRTx surveyed four polling sites in Callahan County, Texas. The P&A found that all four of Callahan County’s polling places had problems with parking, including a lack of accessible parking spaces for lift or ramp equipped vans, inaccessible door handles, and steep slopes.27

One of the polling places DRTx examined had a ramp that measured a slope of around 10 percent. The maximum running slope allowed for ramps is no steeper than 8.33 percent (1:12 ratio). DRTx recommended the County correct the slope in order to meet the ADA requirements or the polling site should be relocated to an accessible location. Acknowledging that the recommendation might seem drastic, DRTx’s HAVA Training & Technical Support Specialist Molly Broadway, LMSW said, “If you aren’t someone who relies on the protections of the ADA for your everyday functioning, I think it’s really easy to say that you’re being persecuted based on this law.”28 Yet, the ADA’s very specific regulations exist for good reason. A ramp with a slope that is too steep can be impossible for a manual wheelchair user to ascend and could be dangerous to descend.

Vermont

In July 2018 Disability Rights Vermont (DRVT), Vermont’s P&A, issued their polling place accessibility report outlining the challenges voters with disabilities experience on Election Day in their state. DRVT found that every county surveyed had polling places that were not ADA-compliant. Compliance problems included a lack of van-accessible parking, inaccessible entrances, and no accessible ramps on election days.29

Beyond Physical Access

Although it is one of the most widely cited reasons why people with disabilities are denied access to America’s electoral system, physical accessibility at polling places is far from the only barrier facing voters with disabilities today. Other barriers include language assistance, lack of knowledge from poll workers (about the right to assistance in casting a vote and how to use accessible voting equipment), and distance to polling places, especially where there are limited public transportation options.

Language Assistance: ASL and Plain Language

Congress expanded the VRA in 1975 and established what is known as the “language minority provision.”30 The language minority provision requires jurisdictions to provide voting materials in English and the language of the applicable minority group in a given area, such as registration or voting notices, forms, instructions, and assistance or information relating to the electoral process and ballots.31 However, when discussing minority languages, election officials and poll workers must remember that American Sign Language (ASL) is a minority language.

The Department of Justice’s ADA guidelines state that “to ensure that voters with disabilities can fully participate in the election process, officials must provide appropriate auxiliary aids and services at each stage of the process, from registering to vote to casting a ballot” and “officials must give primary consideration to the request of the voter.”32 This includes visual instructions at polling places or a poll worker who speaks ASL. However, people must request auxiliary aids and services in advance by contacting their state election officials.33

A voter who does not speak the same language as a poll worker or fully understand the written material both frustrates the voter and can prevent them from receiving legally required auxiliary aids, services, or other accommodations on Election Day. Jurisdictions need to provide materials in plain language which are written clearly, in a logical order, and in an active voice. Plain language voting materials should define terms and abbreviations, and be made available to all poll workers and voters, including those with disabilities.34

Distance

Jurisdictions need to consider the distance required for voters to get to the polls when selecting polling places. Although voters whose polling place is nestled in their home neighborhoods may find it hard to imagine, some voters need to travel over 90 miles to get to their polling place on Election Day.35 It is also important to consider the distance between the polling place and the nearest public transportation stop as some people rely on public transportation to get to the polls, including any voter whose disability prevents driving. While mail-in voting is rising in popularity and commonly offered as a solution to remote or inaccessible polling places, traditional mail voting is also inaccessible for many voters with disabilities, and voters have a legal right to equal access. Unless all voters are expected to mail in a ballot, election officials cannot require one subset of voters to do so. Rather, jurisdictions must strive for equal access at the polls and to the polls.

Absentee and Mail Voting Accessibility

Over the past few election cycles, absentee voting has increased in popularity, and in fact, it is the fastest-growing method of voting in America.36 However, it is not fully accessible. For instance, voters that are blind or low vision, have limited manual dexterity, and other people with disabilities cannot see or physically mark paper ballots independently and privately like other voters who choose to vote by mail.37 The rise of electronic delivery of blank ballots creates opportunities to complete the ballot privately and independently, using personal assistive technology. Yet if voters are expected to print out and return a paper ballot, the process remains inaccessible. While the introduction of electronic transmission has made absentee and mail voting more accessible, it is not a full solution and relies on the voters having access to their own personal technological devices, as well as reliable internet or cellular data service.

Close examination of polling place closures reveals an alarming trend – the ability of states and local jurisdictions to close polling places at their leisure. For years, the federal preclearance provision of the VRA was the law of the land in states like Georgia, Arizona, Mississippi, and jurisdictions in Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and others. However, in 2013 the U.S. Supreme Court changed the course of history with a 5-4 ruling in Shelby County v. Holder by striking down the formula used to require preclearance as set forth in the VRA in any state or jurisdiction with a demonstrated history of discriminatory practices.38

Shelby County v. Holder

On June 25, 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that the “coverage formula” in Section 4(b) of the VRA was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court did not rule on the constitutionality of Section 5 itself, leaving a federal preclearance program intact. Yet, the coverage formula determined which jurisdictions were subject to preclearance under Section 5 of the law. When the Court struck down the primary avenue to determine which states required preclearance, it immediately freed jurisdictions with known discriminatory practices. Today, such jurisdictions no longer need to seek approval before enacting voting changes — including the closure, relocation, and consolidation of their polling places. As a result, the U.S. has seen a dramatic drop in the numbers of polling places across the country over the last few years.39

Polling Place Closures by the Numbers

In September 2019, the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights reported that 1,688 polling places had closed in jurisdictions that were previously under the preclearance requirement of the VRA between 2012 and 2018.40

The U.S. EAC reported that election officials operated 116,990 polling places during the 2016 Election while they operated 119,968 polling places in 2012. The EAC credited this decrease to the expansion of alternative voting options such as absentee, early, and mail voting, as well as transition from traditional polling places to vote centers (a high-capacity polling place where any voter in the entire jurisdiction can choose to vote on Election Day).41

However, the EAC did report in the 2018 Midterm Election that 230,871 polling places were used, an increase from both 2012 and 2016.42 Yet, these figures do not highlight which jurisdictions closed their polling places, and those that increased the number of polling places in use. Essentially, the numbers do not always paint a full portrait of polling place closures in the U.S.43 To illustrate, while some jurisdictions may report a drastic drop in the number of polling places, raw data may not show that the state implemented mail-in balloting for all voters supplemented with a more limited number of voter centers. Additionally, these figures also do not describe the jurisdictions that relocated their polling places, potentially to the detriment of voter access. It is also important to note that jurisdictions self-report their information to the EAC, and the questions jurisdictions are asked to respond to have changed over the years. Qualitative data that tells the stories of these jurisdictions are the best way to truly understand where polling place closures are happening and why.

Polling Place Closures and Relocations: Blamed on the ADA

Alarmingly, recent polling place closures, consolidations, and relocations across the country are being unjustly blamed on the ADA. To be clear, the ADA should never be used as the impetus to close large numbers of polling places. Occasional consolidations or reasonable relocations may be necessary to bring a polling place that always should have been accessible to all into compliance with the ADA. For example, a polling place with a parking area and path of travel located on a steep hillside cannot be temporarily modified or reasonably afford to have the entire grounds leveled. In which case, the polling place may have to be moved to a more accessible location in the immediate vicinity. But ultimately, the way to make polling places accessible is not to close them; it is to make them accessible. The ADA is a civil rights law which mandates equality for all at the polls, and yet shockingly, it has been used in recent years to pit civil and voting rights allies against each other in the struggle for access to the ballot. Jurisdictions and election officials claim that because of the costs associated with making their polling places ADA-compliant, they are better off relocating the polling places, or worse, closing them altogether.

Title II of the ADA mandates that state and local governments do not deny participation in or the benefits of services, programs, or activities of state and local governments to any American, which includes voting in elections. Prior to the ADA, the VAEHA required that polling places also be accessible to people with disabilities dating all the way back to 1984. Essentially, mandating accessible polling places and equal access for voters has been required by law for 35 years. Clearly, given the abysmal rate of ADA-compliance among polling places, jurisdictions across the U.S. continue to act as if they do not need to follow the law.

Jurisdictions that raise their consciousness of ADA regulations and bring their electoral systems into compliance should be recognized for their efforts. Regardless, when a jurisdiction realizes they are not compliant with the law, it does not mean the “best” solution is to close a significant percentage of polling places. In most cases, low-cost permanent or temporary fixes can be made to existing polling places to prevent relocation, consolidation, or closure.

Randolph County, Georgia

The fact that the ADA can be weaponized to close polling places struck a national nerve in August 2018, when a rural county in southern Georgia announced plans to close seven out of only nine polling places in a majority Black community just three months before Election Day. The news of this announcement made national headlines including CNN44, Fox News,45 and the Washington Post.46

In 2018, Randolph County had a population of about 7,224 people across 428 square miles47 In August of that year, the county’s two-member Board of Elections hired a consultant to review the county’s polling places in the hope of saving money. As a result, the election consultant recommended closing all but two polling places, claiming that the seven in question were not ADA-compliant.

The election consultant, Mike Malone, said regarding Randolph County, “The trend in Georgia, and other states, is to reduce the polling places, to reduce election costs, which is natural.”48 Yet, this reasoning stands in direct contradiction to earlier claims of ADA-compliance. Malone failed to produce DOJ-issued ADA surveys of the polling places or any evidence of coordination with disability access experts in making these claims. Options for adapting inaccessible polling places were not considered publicly.

It is also important to acknowledge that in 2018, the state of Georgia was undergoing a heated, historic gubernatorial election with the state’s first-ever female African American candidate to run for governor, Stacy Abrams. Her opponent, Brian Kemp, was Georgia’s Secretary of State at the time — the state’s chief elections official.49 Former Congressman and co-author of the ADA, Tony Coelho commented on the proposed plan and said “[Malone] callously tried to use the ADA as a justification for closing polling locations entirely, which is a violation of the law I and others worked so hard to pass.”50

Following the events in Randolph County, many local and national disability organizations publicly opposed the proposal to close polling places because of ADA-compliance concerns.51 The ARC of Georgia said, “Too many polling places and voting technology throughout the country remain inaccessible. The solution, however, is not to shut down polling places, impacting access to polling places for registered voters with and without disabilities.” 52 Rev Up Georgia stated that the “decision to invoke the ADA to deny other groups’ access to the fundamental right to vote is a total misuse of the ADA and all that it stands for.” 53

Luckily, as a result of national bad press and local activism, Randolph County’s Election Board hastily voted to oppose closing the vast majority of its polling places. However in July 2019, the County announced plans to close three of the county’s polling places — arguing that it will save the county money.54 One article in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported “rather than spend tens of thousands of dollars to make precincts accessible to people with disabilities, the county will save roughly $4,500 per election by closing those polling places.”55 Yet, the county has not explained how these costs were calculated or demonstrated any consultation from the disability community.

Randolph County might have been the one jurisdiction that made national news, but it is far from the only county to attempt to or successfully use the ADA as a tool to close polling places.

Toombs County, Habersham County, and Lumpkin County, Georgia

In late 2014, Habersham County opted to consolidate 14 of its polling places into two, stating that the consolidation was because their existing polling places were not ADA-compliant.56In 2015, Toombs County closed nine of its polling places claiming the county would save close to $200,000 by not making their existing polling places accessible to people with disabilities.57 In 2016, Reuters reported that officials in Lumpkin County consolidated seven out of its eight polling places, in order to make themselves ADA-compliant as well.58

Pearl River County, Mississippi

In October 2017, Pearl River County’s Board of Supervisors discussed reducing its 32 polling places to 20, immediately prior to the county’s Picayune School District Board of Trustees Election set for November that same year. One commissioner of the Board said, regarding opposition to the planned decrease in polling places, “this thing has been a political football. I mean are we going to do what’s the right thing, or what’s the right amount of money? Are we going to cut these things back like we need to or are we just going to bow down to the folks that don’t want to vote somewhere else.”59 Although the reason for the closures was ADA-compliance, Commissioners openly noted that they were not qualified to know whether polling places are accessible to people with disabilities.60

McLennan County, Texas

In July 2018, McLennan County Commissioners wanted to consolidate their polling places “after reviewing security concerns, cost, and accessibility issues.”61 One of their polling places was located in a school, and the school was concerned about the safety of their students. Meanwhile, the Commissioners were also concerned about the costs associated with making the school ADA-compliant. One county Commissioner stated that bringing an existing polling place into ADA compliance “would have cost about $100,000, so moving the vote center will save significant money.”62

Dauphin County, Pennsylvania

In March 2018, Dauphin County voted to merge four of its polling places down to two because of ADA-compliance concerns. The county argued that it made sense to consolidate the polling places because, not only would it address the ADA-compliance concerns, but that one of the polling places already had a low voter turnout and the other had problems finding poll workers. The county noted that some of its polling place remedies were simple and could be completed easily while others could not.63

Baxter County, Arkansas

In 2018, Baxter County opted to cut their polling places by half from 22 to 11, because they wanted to shift to vote centers. However when asked to defend the plan, county officials said “they would have had to shut down 10 polling places anyway, because they were not compliant with the ADA.”64 To Baxter County’s credit, they worked closely with Disability Rights Arkansas, Arkansas’s P&A, to ensure this was the best solution for the county. Ultimately, good planning and opening up the more limited number of locations as vote centers minimized pushback from the community, but the message remained the same “because of the ADA.”

Jefferson Parish, Louisiana

In 2015, Jefferson Parish notified voters they planned to relocate “some polling precincts to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act.”65 This announcement came after the county reached a settlement agreement in a lawsuit, Drake v. Jefferson Parish, brought by a community member with a disability. The Advocacy Center, Louisiana’s P&A who filed the suit, noted that ramps at the county’s polling places were too steep and had no railings that could prevent wheelchair users from “sliding off.”66 The cost of Jefferson Parish’s legal defense would likely have covered the full cost of making the jurisdiction’s polling places accessible, perhaps even saving money in the process. Instead, the county relocated over two dozen of its polling places.67

Richland County, Ohio

In 2015, the Ohio Secretary of State’s Office found that Richland County had ADA-compliance issues at their polling places, including five town halls or fire stations and three churches.68 The ADA-compliance concerns involved no lift or ramp equipped van parking spaces near entrances, inaccessible door handles, and ramps that were too steep for voters in wheelchairs. Although Richland County tried fixing some of the problems highlighted by the Secretary of State’s Office, trustees of the Board of Elections noted, “The state is putting a lot of mandates out. But the townships don’t have a lot of money.” As a result, the county opted to consolidate many of its polling places prior to the 2016 Election.69

Ford County, Kansas

Ford County made news in 2018 for deciding to relocate their only polling place in town to outside of town. The reason for relocating the polling place: the ADA. Furthermore, the closest bus stop to the new polling place was over a mile away. As a result, Ford County had 13,000 registered voters and 1 polling place on Election Day 2018.70 County officials failed to consult with Disability Rights Center of Kansas, Kansas’s P&A, or any other disability advocacy group about the ADA before the polling place was moved.

Department of Justice: Enforcing the ADA

In the rush of media coverage following the controversial plan by Randolph County, investigative journalists called the role of the DOJ to enforce the ADA’s provisions into question. According to a ThinkProgress article, “It’s a diabolical move: citing one civil rights statute (the ADA) as the justification for violating another (the VRA)” and that “these sorts of closures can effectively disenfranchise entire communities of voters, all under the false guise of purportedly seeking to make polling places accessible for the disabled.”71

Over the years, the DOJ has entered into multiple settlement agreements with cities and counties through projects they call “Project Civic Access” and the “ADA Voting Initiative.”

In August 1999, the DOJ reached a settlement with the City of Toledo, Ohio, in which Toledo agreed to remove barriers and relocate activities throughout its city government to ensure equal access to people with disabilities.72 As a result, the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section began similar reviews as a part of Project Civic Access program. The project now includes 221 settlement agreements with 206 localities in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Many of these settlement agreements include polling places.

Project Civic Access, is a wide-ranging effort to ensure that all the services, programs, and activities of state and local governments comply with the ADA “by eliminating physical and communication barriers that prevent people with disabilities from participating fully in community life.” DOJ examines many polling places under the project given that its scope includes physical and architectural barriers. Subsequently, the ADA Voting Initiative focuses on protecting the rights of voters with disabilities specifically and prides itself in working collaboratively with jurisdictions to increase accessibility at the polls. The DOJ, so far has surveyed over 1,600 polling places and increased polling place accessibility in over 35 jurisdictions all over the US.

Despite efforts in the media to tie DOJ intervention to the political whims of any particular presidential administration, the DOJ enforcement actions questioned by the media span multiple administrations. While jurisdictions such as Pearl River County, McLennan County and Dauphin County may claim to have been “targeted” by recent DOJ settlements, there is no clear association between DOJ action and polling place closures that suppress voter turnout. In summary, it is the law of the land for polling places to be accessible under the ADA, and DOJ intervention is an important tool to ensure that compliance.

Rather than forcing polling place closures, DOJ intervention examines each polling place, looking at both temporary and permanent changes needed to comply with the ADA, while keeping polling places open and costs in check. It is, as the DOJ proves, entirely possible to comply with the ADA without closing polling places or breaking the bank.

City of Chicago, Illinois

When it first approached the City of Chicago, the DOJ requested to check 100 of the city’s 1,452 polling places. The initial findings showed that many of the city’s polling places were not ADA-compliant and were inaccessible to people with disabilities. As a result, Chicago’s Board of Election Commissioners, in collaboration with Equip for Equality, the Illinois P&A, and over 200 volunteers and pro bono attorneys checked almost all of the remaining polling places, over 1,000 of them, during the 2016 General Election. Like the DOJ, they found many ADA violations that created barriers to voters with disabilities.

As a result of these findings the Board of Elections and the DOJ reached a settlement agreement in April 2017, under which the city of Chicago willingly agreed to make all of its 1,452 polling places ADA-compliant. In addition to ensuring access for voters with disabilities, the settlement will make the large number of public buildings, that were already required to comply with federal access laws, fully accessible and open up public life more broadly for Chicagoans with disabilities.

Today, many more polling places in Chicago are accessible, with exceedingly few relocations or closures. According to Equip for Equality, the Board of Elections used their experience with the DOJ as an educational opportunity on equal access under the ADA, as well as a chance to educate poll workers and the community.73

Jefferson County, Alabama

During the March 1, 2016 election, the DOJ surveyed 36 out of Jefferson County’s 173 polling places and found that many of them violated the ADA. As a result, Jefferson County agreed to survey the remaining polling places and ensure that all its polling places be fully accessible to people with disabilities in future elections.

According to Barry Stephenson, Jefferson County Board of Registrars chairperson, the DOJ’s investigation into the county’s polling places brought “everyone to the table” and allowed for a productive conversation on what needs to be done.74 This type of collaboration with the disability community had not been seen before, as election officials previously thought they were ADA-compliant. Stephenson even had the opportunity to bring Tate Fall, a disability rights advocate who specializes in voting rights, on board to survey the county’s polling places.

Jefferson County examined its remaining polling places with Fall and found that the majority were not ADA-compliant, as they lacked accessible parking, signs, ramps, or curb cuts. Barry Stephenson said that “most facilities wanted to be compliant too, since the residents are using those facilities every day.”75

Jefferson County noted that geography was key while examining their polling places, as the county is large, and any closures or relocations could have greatly affected its community members and their ability to reach the polls. Yet, the county also realized that many simple fixes were available to become accessible on Election Day. Ultimately, the supplies bought to adapt polling places, such as orange cones to mark accessible parking spaces and access aisles, doorstops to hold open doors that are too heavy, and signs, would represent a significant cost savings over fighting the DOJ in court. According to Barry Stephenson, “in regard to all the supplies we bought for modifications, attorney’s fees would have eaten that up without blinking.”76

Jefferson County also shows that creative solutions are possible for achieving ADA-compliance, even on the tight budget of a predominantly rural local elections official. When faced with the potential closure of a polling place housed in a long-standing church and the realization that an alternate location would be an uncomfortable distance away, Jefferson County elections staff solicited a home improvement chain store to donate lumber and contacted a local Carpenters for Christ group to donate their labor. The county was able to build a permanent, ADA-compliant ramp on a church polling place at no cost.77

Following Jefferson County’s DOJ settlement, the community was able to come together and create a more inclusive environment for everyone. Changes made, like the new church ramp, affected not just Election Day, but every day for Alabamans with disabilities.

Richland County, South Carolina

In June 2016, the DOJ surveyed 54 of Richland County’s 150 polling places.78 The majority of the polling places surveyed were not ADA-compliant. As a result, the South Carolina County entered into a settlement agreement with the DOJ to ensure future ADA-compliance.79 Richland County agreed to use portable ramps (including curb ramps), portable wedges or wedge ramps, floor mats, traffic cones, and other temporary fixes to address the needs of inaccessible polling places.80

The South Carolina P&A had said for years that Richland County had several inaccessible polling places and was happy to see the agreement.81 The P&A also noted that because of the settlement agreement, other South Carolina counties stepped up and worked to ensure accessibility in their jurisdictions as well, to prevent DOJ intervention. Whether it was for fear of being sued, lack of knowledge about compliance, or the willingness to ensure access at the ballot box, DOJ’s enforcement efforts had a positive impact on many voters with disabilities in South Carolina and resulted in other counties also making their polling places accessible on Election Day.

Anderson County, South Carolina

In November 2018, the DOJ announced a settlement agreement with Anderson County, South Carolina following a survey of the county’s polling places.82 The DOJ surveyed 15 polling places in Anderson County and concluded that many were inaccessible to voters with disabilities. Katy Smith, Anderson County’s Elections Director, noted that the county did not realize they were doing anything wrong prior to working with DOJ, but viewed their experience with the DOJ as an important educational opportunity.83

One voter in Anderson County, who is a wheelchair user, had to wait up to 45 minutes at a polling place in an attempt to vote using curbside voting prior to the DOJ settlement agreement and had even filed a complaint with the Department in 2016.84 The voter noted, “I shouldn’t have to do curbside. I’d have been happy to park and get out with everybody else. That’s part of the experience. I shouldn’t have to ask other voters to go inside and get poll workers to help me.”85

Harris County, Texas

In March 2019, the DOJ announced a settlement agreement with Harris County, Texas under the ADA Voting Initiative.86 The county has over 750 polling places. The DOJ noted that the county violated the ADA by using ramps that were too steep, sidewalks and walkways with dangerous gaps, and locked gates along paths of travel barring pedestrian access.87

Disability Rights Texas (DRTx) attempted to contact Harris County multiple times to support making their polling places ADA-compliant prior to DOJ intervention.88 The county did not respond, despite the fact that DRTx offers their services free of charge. However, the DOJ has since commended Harris County for willingly entering into the settlement agreement.

City of Chesapeake, Virginia

In May 2017, the DOJ announced a settlement agreement with the City of Chesapeake, Virginia following its survey of 20 of the City’s 64 polling places. The Department found that the majority of the city’s polling places violated the ADA, and as a result, the city agreed to change their voting system in the years ahead to comply with the ADA.89

McKinley County, New Mexico

In June 2019, the DOJ announced a settlement agreement with McKinley County, New Mexico. Zuni Pueblo and portions of the Navajo Nation are a part of the county, and over 20 of the county’s polling places are located on tribal land.90 The DOJ indicated they had received a complaint and as a result surveyed 32 of the county’s then 47 total polling places. The Department found that many of the polling places had barriers to people with disabilities and entered into an agreement with the county to ensure that they install temporary measures and/or permanent solutions to all of its 47 polling places.91

Coconino County, Arizona: A Closer Look

Four sovereign nations, Navajo, Hopi, the San Juan Southern Paiute, and the Havasupai Tribe, are located within Coconino County, Arizona. Coconino County is the second largest county in the U.S. by area, following San Bernardino, California. Coconino County itself is even larger than some states, including Maryland and New Jersey. The Navajo Nation land area, within Arizona, alone is larger than the state of Connecticut. The population in Coconino County, as of 2018, was approximately 142,854—with 27.6 percent of the population identifying as Native American.92 With much of the land being owned by the various Sovereign Nations in the county, only 12 percent of the land is private taxable property. In addition, there are many spoken languages including various primarily oral languages. Notably, there is a large University population located in Coconino County, Northern Arizona University (NAU), and the Grand Canyon is located within the jurisdiction of Coconino County.

A large geographical area with extremely rural areas, the physically challenging land of the Grand Canyon, limited resources, and a diverse population are some of the factors that play a key role in the decisions Coconino County election officials make in the administration of elections. Coconino County has been cited in recent years for polling place closures allegedly related to DOJ enforcement. Yet, Coconino County’s journey to elections accessibility presents itself as one that is far from finished, and the elections officials themselves are working actively with tribal leadership to find creative solutions for a challenging setting.

BACKGROUND

Even after ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution in 1868, Native American men still did not have the right to vote, let alone Native American women. Native Americans were finally granted official U.S. citizenship in 1924 when Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, also known as the Snyder Act.93 It should be noted that despite the Snyder Act, Native Americans will always have a haunted legacy of being separated from their own culture in order to make them more “American.”94

Today, 567 Sovereign Nations across the entire U.S. have a formal nation-to-nation relationship with the U.S. government, with a total land mass of over 100 million acres.95 The Navajo Nation located in areas of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico would be the 42nd largest state in the U.S., alone larger than states like Maryland, New Hampshire, and Hawaii. While tribal lands are exempted from Titles I and II of the ADA, there is legal precedent to suggest that Title III of the ADA applies to public accommodations in reservations.96 Further, federal elections funded with government dollars must fully comply with ADA’s regulations

DOJ SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT

In August 2016, as a part of the DOJ’s ADA Voting Initiative, the Department surveyed 31 of Coconino County’s 61 polling places. As with most jurisdictions, the DOJ found that many of Coconino County’s polling places were not ADA-compliant. Most of Coconino County’s polling places lacked van accessible parking, appropriate signage, and accessible door hardware.97

Almost two years later, in May 2018, the DOJ announced a settlement agreement with Coconino County. As a result, Coconino County agreed to start adapting their polling places to ensure that all sites are accessible to people with disabilities before the November 2020 election.98 The agreement noted that the county is not limited “from making ADA-compliant, permanent modifications to its polling place locations instead of providing temporary remedial measures or relocating a polling place location.”99

The DOJ settlement did not list how many of the polling places surveyed lacked ADA-compliance. Rather, the settlement states “that many of the County’s precincts and early voting locations are housed in polling places which contain barriers to access for persons with disabilities, and that Coconino County violated Title II by failing to select and use facilities as polling places on Election Day that are accessible to persons with disabilities.”100 However, Type Investigations (a program of Type Media Center, a nonprofit media center) reported in November 2018 that, following the settlement, Coconino County reviewed the additional polling places and found that 46 of the total 65 polling places at the time were not ADA-complaint.101 In other words, over half of the county’s polling places were, in some way, inaccessible to people with disabilities.

Following the news of the settlement agreement, the DOJ received accusations that it was targeting Coconino County and that DOJ enforcement would lead to polling place closures to suppress the Native American vote.102 Opponents expressed concerns that the Department’s efforts would hinder opening future polling places and early voting sites that serve Indigenous communities.103

COCONINO COUNTY’S POLLING PLACES

As of September 2019, Coconino County has a total of 71 precincts, 54 polling places, and 3 vote centers (Tuba City High School, Flagstaff Mall, and J. Lawrence Walkup Skydome). The Sovereign Nations (Navajo, Hopi, the San Juan Southern Paiute, and the Havasupai Tribe) are located among 15 of the total precincts in the county. Thirteen polling places and two of the vote centers, Tuba City High School and Flagstaff Mall, serve the reservations as well.104

The Leadership Conference reported that Coconino County’s polling places went from 64 to 55 between 2012 and 2018.105 During the 2016 Election, Coconino County had 61 polling places according to the DOJ, and in September 2019, Coconino County reported that they had 54 polling places. Coconino County stated the decrease in polling places was mostly as a result of consolidations, vote centers, and certain polling places that had to be closed because of safety concerns, including locations that were being condemned.106

High Country News reported that following the settlement agreement with the DOJ, Coconino County had a total of five polling places that could not be updated to meet the requirements of the ADA and had to be relocated; the farthest moving roughly 10 miles away from its original location.107 According to the Coconino County’s election officials, the Inscription House polling place located on the Navajo Nation was just moved across the street based on request of the Chapter Manager. The polling place in Leupp’s Community building was closed in 2016 due to unsanitary conditions, while the polling place in Tonalea’s Chapter House was moved to a different building on the same Chapter House campus.

Election officials in Coconino County also opted to consolidate three of their polling places in Tuba City into one, as two of the polling places were no longer usable. Coconino County’s Tuba City Elementary School was new, but lacked sufficient parking, and became too crowded for it to be a polling place. Tuba City Junior High School’s polling place also had limited parking. As a result, Coconino County consolidated these two polling places with Tuba City’s high school. Tuba City Elementary School is approximately 1.6 miles away from the high school, while Tuba City Junior High School is about 1.8 miles from the high school.