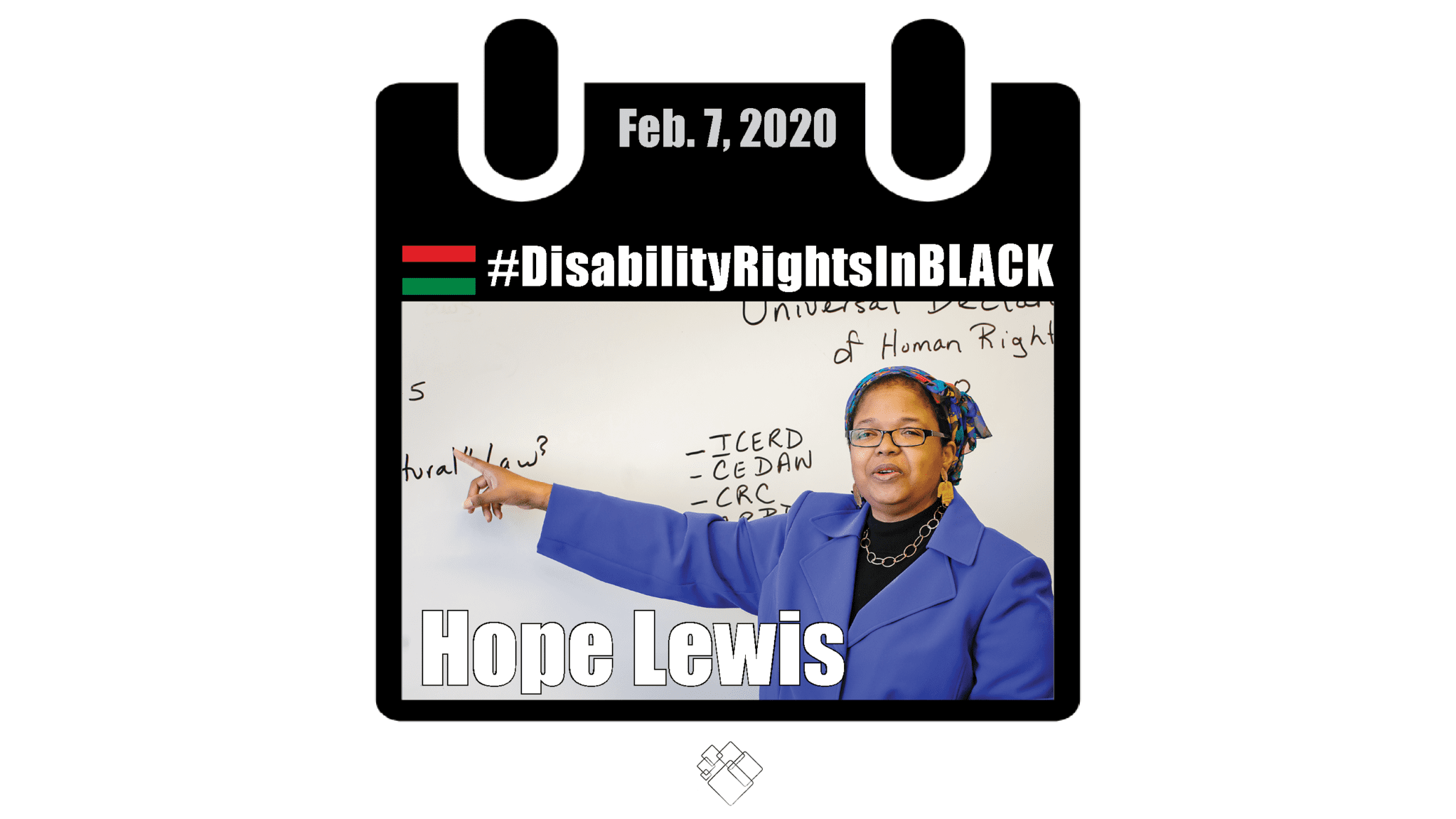

Today, we celebrate Black History Month in remembrance of Hope Lewis. As a distinguished law professor at Northeastern University, Professor Lewis’ work often addressed critical issues at the intersection of race, gender, disability, and poverty. She co-authored the seminal textbook Human Rights & The Global Marketplace: Economic, Social and Cultural Dimensions (2005) as well as several frequently cited scholarly articles such as Forgotten Sisters: Disability Rights of Global Women.

Although Professor Lewis passed away in 2016, her continual efforts to protect the human and economic rights of impoverished/marginalized people still live on around the world through her legal research, teachings and prolific advocacy. Check out this video message for some enduring advice from Professor Lewis read and performed by NDRN staffer LaToya Blizzard. Photos of Hope Lewis provided by Northeastern University.

Share our tribute to Hope Lewis on Facebook and Twitter.

Video Transcript

Hi, my name is LaToya Blizzard and it’s my pleasure to voice some of Professor Hope Lewis’s advice to future women lawyers of color with disabilities. The following words of wisdom were taken from her essay To My Sisters-in-Law (Teaching) – A Critical Race Feminist Perspective which appeared in the highly helpful book Lawyers, Lead On: Lawyers with Disabilities Share Their Insights.

Living in the intersection: Don’t get run over

Critical Race theorists use “intersectionality” as a helpful analytical framework. Your identities as a person of color, a woman, a person with a disability, and a law professor each bring with them ever-changing challenges and opportunities. No matter how you see yourself, others may be socialized to see you only through one or more of these lenses. It’s not always clear which one is dominant at any given moment. Being a member of more than one marginalized group can mean that the specific, compound nature of the discrimination you face is never fully addressed. Maintain the freedom to be all of the identities that inform your individuality as well as your participation in various socially constructed communities.

Ask the other question

Critical Race theorist Mari J. Matsuda urges readers to “ask the other question” when analyzing social justice issues. This is excellent advice for people from marginalized groups. It is also an important lesson for progressive activists who might fail to become more aware of how they might marginalize others in turn. In a context where “neutral” considerations are on the table, ask about gender implications. When gender or sexual orientation is at the center of the discussion, ask about racial, ethnic, or cultural implications. When race is on the agenda, ask about the implications for persons of color with disabilities.

Work with mentors

Critical Race theorists have written about the potential and perils of being a role model for other women teachers of color. We can learn a great deal from those we emulate, but we cannot assume that, because they did things a certain way, we should do the same. Nor should we assume, if they show human foibles, that our own goals are meaningless or unachievable. Still, we all need mentors. Those we choose to mentor us may not share our identities, but seek out those who have the sensitivity and openness to learn about them and the willingness to share positive strategies.

It was because I had worked with blind attorneys in a federal agency that I believed it was possible to continue my law career when I first became vision-impaired. Disability organizations introduced me to blind litigators, sole practitioners, judges, and, most importantly, professors. I haunted them with questions about teaching strategies, the latest technologies, and the state of the law. Their generosity of spirit and leadership in their fields provided the concrete evidence that what seemed overwhelming—and sometimes still does—is possible.

Tell your own story

Storytelling methodology is another creative contribution of Critical Race Theory. Anecdotal evidence can be misleading when too easily extrapolated to an entire group. Nevertheless, subordinated groups find that legal scholarship can marginalize their lived realities. Telling evocative individual stories can spark recognition and open the door to further scholarly inquiry and legal reforms. Storytelling builds awareness of previously ignored issues.

Most important, don’t forget who you are and the talent, hard work, and trailblazers who helped get you where you want to be.

Peace,

Hope Lewis